The Birth of Meiji Chocolate: Colonial Taiwan and Its Sugar Industry

Taiwan’s sugar industry flourished during the Japanese colonial era, giving birth to the widely known chocolate brand: Meiji Chocolate. A story about Japanese colonial modernity and anti-colonial resistance in Taiwan, this article on sugar features as part of our new special issue: Encountering Everyday Life: Taiwan in Museums.

By Chen Li-hang (陳力航)

Translated by: Grace Ho Lan Chong

Edited by: Yu-Han Huang and Sabrina Teng-io Chung

This piece was originally published by the National Museum of Taiwan History. It was translated and published with the permission of the copyright owner.

Whenever sugar is mentioned, what comes to mind is the commonly used granulated sugar, white sugar, and brown sugar. However, our relationship with the sugar industry is more intertwined than expected. In the past, cut sugarcane was often sold as roadside wares, purchased by the bag to eat as a snack while one watches TV. Elders might also tell stories of their youth: waiting beside the railway for small trains carrying sugarcane to pass by, they would steal sugarcane to eat. But you might not have known that the Taiwanese sugar industry actually thrived during the Japanese colonial era, during which the widely known Meiji chocolate was born.

IMPORTANT SUGAR INDUSTRY IN TAIWAN

During the Japanese colonial era, sugarcane was an important Taiwanese crop, just as the sugar industry was a key industry in Taiwan. An old saying notes, “Only the foolish plants sugarcane for sugar companies.” This Taiwanese adage reveals the hardship of Taiwanese sugarcane farmers under Japanese rule. Specifically, it references the 1925 Erlin Sugarcane Farmer Incident that took place in the mid-Taiwan region, Changhua.

Before going into the details of the Erlin Incident, we should give attention to the “Raw Material Collection Area” system of the Government-General of Taiwan (臺灣總督府). From the perspective of sugarcane farmers, the mandate of the Raw Material Collection Area prevented them from freely disposing their crops. They could only hand over the sugarcane to designated sugar companies. The Erlin Incident was a conflict that resulted from a sugarcane acquisition dispute. Starting from 1923, sugarcane farmers in the area had been continuously petitioning the Khe-tsiu Sugar Refinery (溪洲糖廠), which belonged to Lîm Pún-guân Sugar Manufacturing Co., Ltd (林本源製糖株式會社), for raising the purchase price of sugarcane. However, the refinery neglected their requests. In early 1925, to unite the farmers, Lí Ing-tsiong (李應章), Tân Bān-khîn (陳萬勤), Lâu Siông-hú (劉崧甫), Tsiam Ik-hôo (詹益侯), and others established the Erlin Sugarcane Farmer Association (二林蔗農組合), a group that eventually grew to over 400 members.

The Erlin Sugarcane Farmer Association negotiated with the sugar refinery to raise the price to no avail. However, at the end of the year, the staff of the Sugar Manufacturing Company arrived in the sugarcane fields to harvest on their own. A physical conflict broke out between the staff and the farmers. This resulted in the arrest of the leader Lí and other cadres of the association. This conflict is now known as the Erlin Incident. Fortunately, two lawyers of the Japanese Labor Party (日本勞動黨), Fuse Tatsuji (布施辰治) and Asō Hisashi (麻生久), stood in support of the sugarcane farmers. There were also Taiwanese lawyers, Tém Siông-ûn (鄭松筠) and Tshuà Sik-kok (蔡式穀) who defended for the farmers in court. According to the verdict, Lí was sentenced to eight months, the longest among all, whereas other members, including Lâu and Tsiam, were sentenced to two. The Erlin Incident can be described as the beginning of the peasant movement in colonial Taiwan.

Farmlands of the sugar companies (Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Collection Number 2001.008.0081.0027)

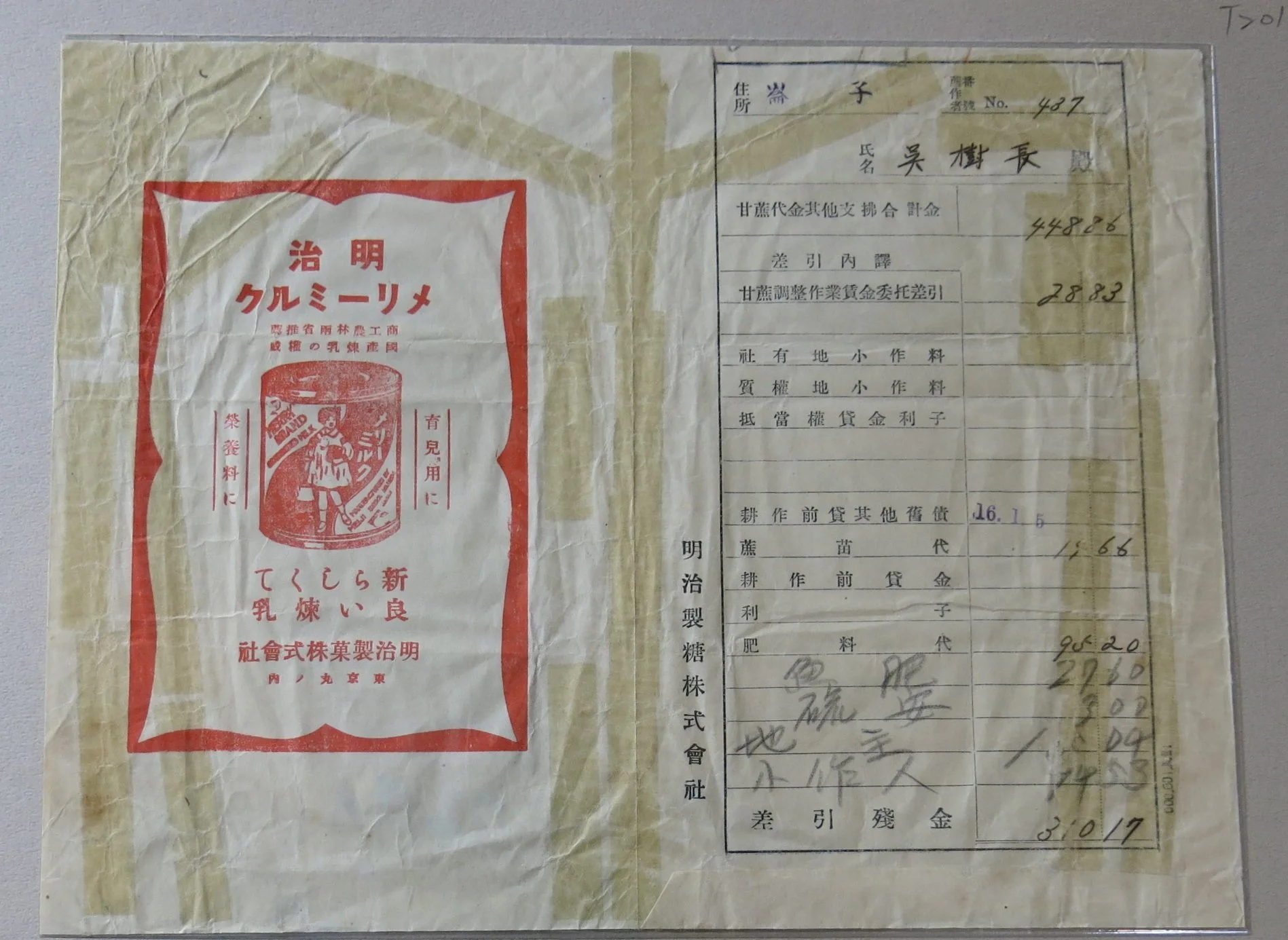

A Meiji Sugar Manufacturing Co., Ltd.-issued cash bag for sugarcane farmers when purchasing sugarcane. The other side was an advertisement for Meiji Seika condensed milk. (Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Tentative Collection Number T2018.001.8078)

THE BIRTH OF MEIJI CHOCOLATE

During the Japanese colonial era, the primary business of the majority of Taiwanese sugar companies exported raw sugar to mainland Japan. However, several sugar companies were affected by the ups and downs of the sugar industry. They began to consider integrating upstream and downstream production. One of the earliest pioneers was Meiji Sugar Manufacturing Co., Ltd (明治製糖株式會社), the development of which was related to the Meiji Chocolate.

The Meiji Sugar Manufacturing Co., Ltd was established in 1906. Its president, Sōma Hanji (相馬半治), had travelled to Europe and the United States to learn about the sugar industry in the earlier years. Later, due to the Russo-Japanese War, he relocated to Taiwan. The Meiji Sugar Manufacturing Co., Ltd flourished, leading to further expansion of its business to the manufacturing of snacks and dairy products. Under this context, Meiji Seika Co., Ltd. was established in 1917. Its main products were divided into two categories. The first was snack food and soft drinks, such as Meiji chocolate, yogan, fudge, soda, and other products. This was followed by dairy products, including Meiji milk, butter, cheese, ice cream, condensed milk, and more. There was a dazzling array of products. In fact, these products are still available today, among which, Meiji chocolate stands out as one of the most representative products. To a child, a piece of Meiji chocolate can bring immense happiness.

DELICIOUS AND FUN: THE SWEET TIME TO ENJOY MEIJI CHOCOLATE

Meiji Chocolate launched a promotion of collecting kanji cards to attract children. A resident in Giran County (present-day Yilan), Tân Í-bûn (陳以文), was a fan of Meiji chocolate. He was born to a wealthy family during the Japanese colonial era. His father, Tân Thóo-kim (陳土金), was a well-known Western medicine doctor in Giran County. With this family background, he could easily get hold of a piece of Meiji chocolate. Tân recalled, “At that time, I really liked eating Meiji chocolate. The package was similar to the current one. There would be a kanji card hidden in each package. If you collected five different kanji cards, you could get another chocolate bar for free.” Similar promotions still exist today. What’s amusing is that one card would always be missing during the process, and one could never collect them all.

In addition to the chocolate bars, the outer container was also a collectible item to many people at the time. In the collection of the National Museum of Taiwan History, there is a glass jar for sweets and biscuits from the Meiji Seika Co., Ltd. According to the collector, this item probably did not belong to Taiwanese grocery stores. Although there were also candy jars in Taiwanese grocery stores, the list of items in the jars was usually handwritten on paper then pasted onto the jar. This way, the jar could be used for all kinds of contents by simply replacing the paper label on the jar (similar to the tea storage containers in traditional tea shops with a variety of tea labels). As such, it was quite rare to have the brand or product name printed directly onto the jar. Therefore, this jar most likely came from Japan or the Meiji Seika store in Sakae-machioh of Taihoku (present-day Taipei) during the Japanese colonial era.

Candy and Biscuit Glass Jar of Meiji Seika Co., Ltd. (Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Tentative Number T2018.001.1563)

If you have watched Japanese TV or anime series before, you might have seen a rotary machine that is used for lucky draws in shopping streets. There are many numbered balls inside the machine. The prize is then determined by the numbered ball that falls out. As the machine spins, both adults and children will wait with bated breath. After buying chocolate or candy, the lucky draw can excite people more so than the taste of the sweets. The machine is called the Arai rotary lottery machine (新井式回転抽選器) and is one of the many collection items of the National Museum of Taiwan History.

Arai rotary lottery machine (Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Collection Number 2017.017.0013)

Numbered balls of Arai rotary lottery machine ( Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Collection Number 2017.017.013.0002)

Some people bought chocolates in Taiwan hoping to win a prize, while others flew directly to the Meiji Seika headquarter in Japan. During the Japanese colonial era, a member of the Taiwanese gentry, Tíunn Lê-tsùn (張麗俊), chose to visit the factory of Meiji Seika in Tokyo. Tíunn is a native of Toyohara in Taichū (now Fengyuan District in Taichung City). Through his diary, we can see if the “travel notes” penned by Taiwanese travelling to Japan some eighty to ninety years ago are consistent with modern day travelling blogs. On April 16, 1935, after visiting the official residence of the Governor-General, Nogi Maresuke (乃木希典), Tíunn drove to the Meiji Seika Co., Ltd. He wrote in his diary, “ I then took a car to the Meiji Seika factory and enjoyed the sweets and tea served there. The factory director boasted that the raw materials they used came from Southeast Asia. When our tour guide Sato heard this mistake he made, he couldn’t help but scoff at him.” This scene of a guided factory visit where visitors dropped their causal comments along the way somehow resembles current tour groups of our day.

Relevant Museum Collections:

Meiji Chocolate Airplane Pin (Source: National Museum of Taiwan History, Collection Number 2004.007.0180)

Reference:

Cai Hui-pin, “Japanese Lawyers and the Peasant Movement in Taiwan,” Newsletter of Taiwan Studies, 105 (May 16, 2018), pp. 18-19.

Wu Mi-cha ed., Keywords for Taiwanese History (Taipei: Yuan-Liu Publishing Co., Ltd., 2000), pp. 134-135.

Meiji Sugar Co., Ltd. ed., Thirty Years of Meiji Sugar Corporation (Tokyo: Meiji Sugar Tokyo Office, 1936), pp. 112-137.

Chen Li-hang, “Interview Record of Mr. Tân Í-bûn,” The I-Lan Journal of History, 87, 88 (2011), p. 141.

Chen Li-hang, “Interview Record of Mr. Lin Yu-xin,” unpublished, interviewed on November 6, 2020.

Zhang Lijun, Xu Xueji et al. ed., “Owner’s Diary of Shui Zhuju /1935-04-16,” Taiwan Diary Knowledge Base of the Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica, published online on November 6, 2020. https://taco.ith.sinica.edu.tw/tdk /Shuizhuju owner's diary/1935-04-16