Mediating Japan’s Southern Advance: An Interview with Seiji Shirane (Part 2)

We are pleased to discuss with Professor Seiji Shirane the intermediary role of colonial Taiwan and overseas Taiwanese subjects in the Japanese Empire’s southern advance in South China and Southeast Asia.

Professor Shirane is a historian of modern Japan at The City College of New York (CUNY). His first book is Imperial Gateway: Colonial Taiwan and Japan’s Expansion in South China and Southeast Asia, 1895–1945 (Cornell University Press, 2022). His research has received support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Fulbright, Social Science Research Council, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The interview was conducted online in English on February 2, 2023 and has been edited for clarity. The interview is published in two parts. Part 1 details Professor Shirane’s academic trajectory and the historiographical interventions that his scholarship builds on and further extends. Part 2 covers Professor Shirane’s thoughts on his book’s potential reception in Taiwan, his pedagogical and historiographical interventions in the field of modern Japanese history, the goals of the newly founded Modern Japan History Association (MJHA), and his advice to graduate students studying Taiwan history in North America.

Interviewed and edited by Sabrina Teng-io Chung

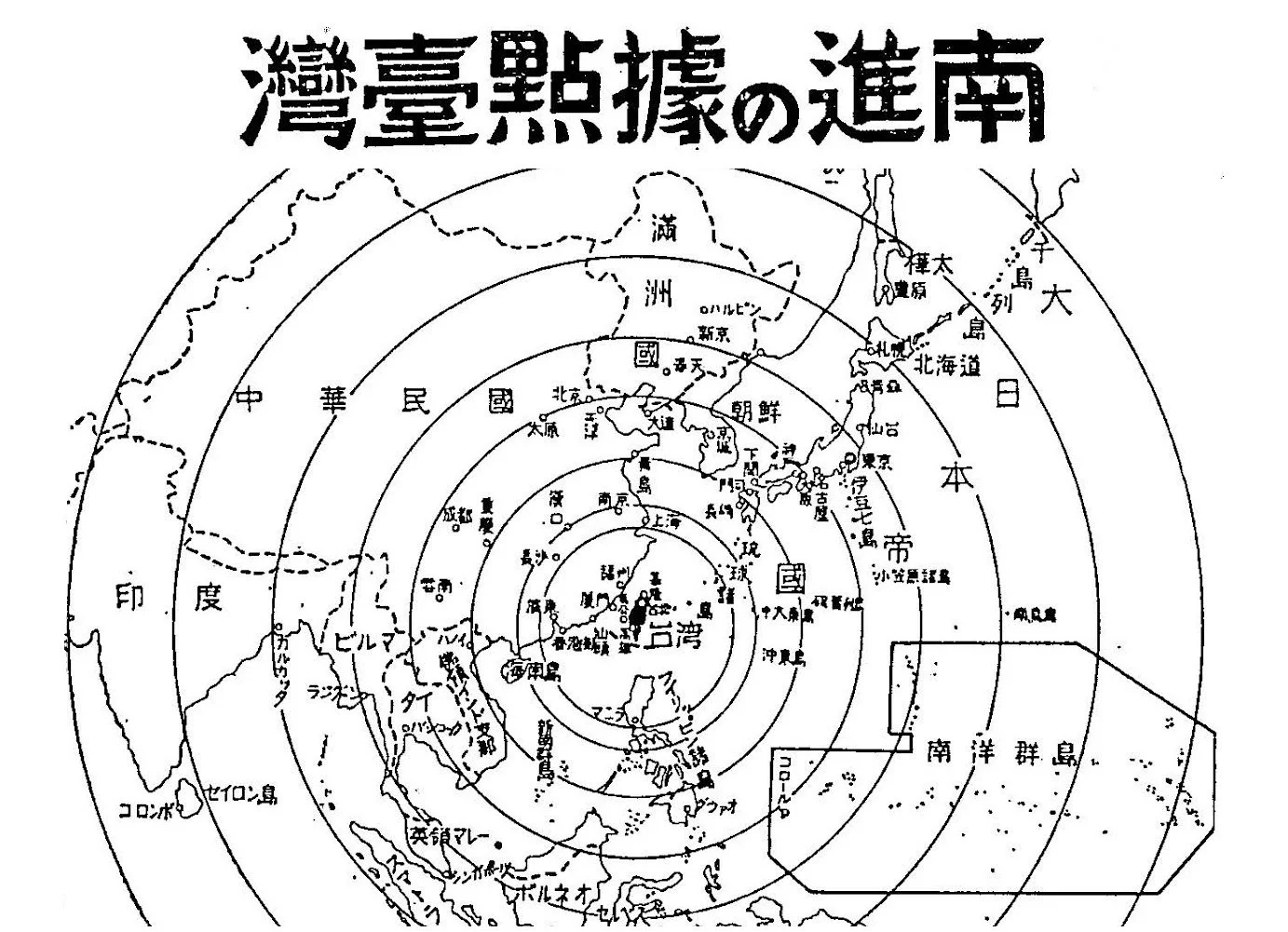

Cover image: Taiwan Government-General map titled “Taiwan as [Japan’s] Base for Southern Expansion.” Source: Taiwan Sōtokufu Rinji Jōhōbu, “Nanshin no kyoten Taiwan,” Buhō, no. 63 (June 1939).

Taiwan Gazette: Can you share with us your expectations of how your book might be received in Taiwan? We know that Linking Publishing (聯經出版) is working on a Chinese-language translation of your book.

Seiji Shirane: On August 3, I will be giving an in-person talk at Academia Sinica’s Institute for Taiwan History, where I was affiliated in 2010-11. That’s where I will explain in Chinese how my work is building on but differing from existing Chinese-language scholarship on colonial Taiwan.

As I mentioned earlier, my work is indebted to the scholarship of Taiwanese scholars especially Chung Shu-min, Hsu Hsueh-chi, Chang Lung-chih, Mike Shi-chi Lan, and many others. I think my main contribution to existing Taiwanese scholarship is my framework of conceptualizing Taiwan as an imperial gateway through which to understand intra-imperial rivalries within, and inter-imperial rivalries outside, the Japanese Empire. I also think my multi-lingual and multi-archival approach that makes use of not only Japanese, Taiwanese, and Chinese sources, but also British, American, and Singaporean sources is something that has not been done by previous scholars in Taiwan. The temporal and geographical scope of my book over fifty years also illuminates both changes and continuities in Japan’s southern advance and the role of the overseas Taiwanese in South China and Southeast Asia.

I hope that the combination of sources and the conceptual framework of my book will be useful to the Taiwanese scholarly community. My Japanese mentor Kawashima Shin (University of Tokyo) once told me that the role of a non-Taiwanese scholar is not only to introduce Taiwan history and scholarship to the outside world, but also, in some ways, to introduce broader Anglophone and Japanese-language approaches to the Taiwanese community. For example, Taiwanese scholars might not be as familiar with the study of Korean migration, Indian migration, or global empires. Having put the case of colonial Taiwan in dialogue with multiple bodies of scholarship, I hope my book can contribute to the existing literature by Taiwanese scholars.

In terms of the book’s Chinese-language translation with Linking Publishing, my hope is to make my work more available to a Taiwanese public that does not necessarily read English. I hope to direct greater attention to the regional dynamics that shaped colonial Taiwan’s intermediary role in Japan’s southern expansion in South China and Southeast Asia.

Taiwan Gazette: How would you expect the book promotion to proceed in Taiwan? Will it be targeting the academic community or the general audience?

Seiji Shirane: Linking Publishing is a trade press that publishes serious academic work. Tu Feng-en (涂豐恩), the editor-in-chief of the press and founder of the online public history platform called StoryStudio (故事), is very creative in terms of cutting-edge ways of publishing and making public history more accessible in Taiwan. I trust his judgment in terms of how Linking Publishing can creatively promote the book.

Generally speaking, I think social media has really helped and changed the ways of disseminating and publicizing our books. In decades past, we relied on publisher catalogs and book exhibitions at conferences. But now, it’s quite easy to follow new publications in the field through various channels on social media. Word spreads very fast, both in English and Chinese social media worlds, if there’s an announcement about a new book.

Taiwan Gazette: Can you share with us your experiences teaching the history of modern Japan, war, and imperialism? How have your students received your scholarship or the historiographical interventions you are trying to make in modern Japanese history?

Seiji Shirane: First, in the acknowledgements of my book, I thank the undergraduate and graduate students who took my classes on “The Japanese Empire” and “Asia-Pacific War.” They gave me serious feedback whenever I assigned chapters or different versions of my manuscript in class. They really helped me improve the book by pointing out areas that needed more explanation or less detail, etc., and I am thankful for that. In addition, it’s been great practice for me to present the history of colonial Taiwan and the Japanese Empire to my students who do not have much background knowledge about the subject matter.

What I want my students to get from my classes is similar to what I seek to contribute to the field of modern Japanese history— to understand how places and peoples outside of Japan proper have been crucial to the making of the Japanese Empire specifically and East and Southeast Asian histories generally. It’s important to give voice to protagonists and agents who are non-Japanese, to really understand the multiethnic and multiregional nature of the Japanese Empire and its histories. Why is Taiwan important? Well, it’s important to understand Japan’s southern empire and its regional dynamics. Without a focus on Taiwan, we cannot truly understand Japan’s prewar and wartime dynamics in South China and Southeast Asia. In this sense, my teaching and historiographical intervention to the field of modern Japanese history is one and the same: to reveal the interconnectedness of the regions and peoples crucial to Japan’s empire-building.

The previous generation of scholars from the 1980s to 90s often conducted research on the Japanese Empire based on Japanese-language sources and scholarship alone. Over the past decade or so, however, it has become standard for historians in the field to use at least another Asian language for their research. I think teaching and researching modern Japanese history with a multilingual, multiethnic, and multiregional framework is now more of a common approach. There’s also a need to think of new pedagogical and historiographical approaches to the study of Japan because of the so-called “decline” of Japan studies. With growing interest in China (and Korea) over the past few decades and fewer job openings in Japan studies, Japan scholars need to develop a multiregional approach to their research and teaching that shows how important Japan has been (and continues to be) in regional and global contexts.

Taiwanese servicemen in the Japanese Imperial Army. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Taiwan Gazette: This is a follow-up question about your teaching. Has the COVID-19 pandemic or rise of anti-Asian racism in the US affected your students’ understanding of the Japanese Empire? Did they raise questions about Japan’s management of its minority populations, or the kind of racism that Japan as a multiethnic empire directed towards its minority populations?

Seiji Shirane: I hadn’t previously thought of this question in terms of the pandemic and anti-Asian sentiment and its effects on the classroom dynamic. I will first say that I’m very fortunate and privileged not to have encountered anti-Asian racism and sentiments so far, both in New York City where I live, and in CUNY where approximately 80% of the student population is non-white. Things might have been very different had I lived in a different region of the US with a different student population.

In terms of teaching, my goals have always been to discuss racial issues in Japan, especially those of the Japanese Empire. Many of my students are first- or second-generation immigrants and they are certainly well-versed in issues of race and migration in the US context. They can thus relate to the topic and have a lot to talk about, both personally and academically. So, I would say that students have been just as interested in the issues of Japan’s treatment of its minority populations, Pan-Asianism, and racial rhetoric before and after 2019. In some ways, I am glad that the pandemic and racial politics in the US has not really changed the class dynamics for me and my students.

Taiwan Gazette: We still have a question about the Modern Japan History Association (MJHA). Can you share with us the mission of the Association? From my understanding, much of its activities take place online. How has the online environment enabled or facilitated the Association’s outreach to its members?

Seiji Shirane: The Modern Japan History Association (MJHA) is a newly formed non-profit organization for scholars interested in modern Japan and Japanese history. There are over 150 scholars in North America who teach and conduct research on modern Japanese history. This number does not encompass those who are interested in, or teach modern Japan in the disciplines of anthropology, literary studies, cultural studies, among others. And if we look globally, there is really a huge community of Anglophone scholars teaching and conducting research on modern Japan in Europe and Asia. Despite the existence of this community, there hasn’t been a professional association to unite and mobilize these networks for academic purposes.

During the pandemic, a lot of wonderful publications on modern Japan came out but in-person book talks were suspended. So, Benjamin Uchiyama from the University of Southern California and Nick Kapur from Rutgers University-Camden began to host online book talks. The MJHA has continued to host 3-4 book talks every semester with discussants. My virtual book launch in December 2022 with Professor Andrew Gordon as discussant resulted in a fruitful academic exchange with a large audience across North America. I believe this series can continue to showcase exciting new books in modern Japanese history.

Professor Shirane’s virtual book launch co-hosted by the Modern Japan History Association.

In recent years, the Association for Asian Studies (AAS) conference has hosted roundtables that ask: How do we deal with the “decline” of Japan studies? Indeed, with the rising importance of China studies, we need to continue to strengthen institutional and academic support to keep Japan studies relevant in academia and the greater public. Hopefully, the MJHA can create research and teaching resource networks, an annual distinguished lecture, and annual prizes for a modern Japanese history book and dissertation to promote scholarly engagement with the field.

Taiwan Gazette: We would like to end the interview with any advice to graduate students studying Taiwan history in North America.

Seiji Shirane: The North American Taiwan Studies Association (NATSA) has a panel or workshop on what to do in terms of job hunting and promoting Taiwan studies every year. I was very privileged to be invited to attend the annual conference in 2019. Back then I shared my thoughts about how students really need to show how the case of Taiwan is important to regional or global issues and to larger fields of study, be it Japan studies or China studies. Unfortunately, there are few “Taiwan Studies” positions in North America like those at the University of Washington (James Lin, for example, is the first faculty to be hired as part of the University of Washington’s Taiwan Studies Program). We have to deal with the reality that most students have to find jobs within the conventional fields of Japan, China, or East Asian regional studies.

During my own graduate studies, I had mentors who warned that it would be challenging to get a job in China or Japan studies if my dissertation focused solely on Taiwan. For me, it was less of a problem because I am trained as a Japan specialist. One of the great things about the recent scholarly generation is that we have way more graduate students and young scholars in the field of Japanese history who are from Korea, Taiwan, and China with Japanese-language abilities. But I do think that if you are a Taiwanese student or scholar of Japan or China, your knowledge and expertise of your major field (be it Japan or China) will be tested, which is good since you want to show how research on Taiwan matters to larger regional issues for both intellectual and job hunting purposes.

I would also say that for graduate students who are potentially interested in academic jobs outside North America (especially with the challenging job market), it’s important to stay connected to academic networks in Taiwan (and other parts in Asia one might want to work in). In Japan and Taiwan, for example, the job market is also incredibly competitive and personal and academic connections matter. So, whether it’s through conferences or research trips to Asia, it’s important to stay connected so that you can gather information about job openings and potentially get a reference letter from local scholars in Asia. Today, more than ever, there are really great academics with North American PhDs that have good jobs in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, China, and Japan, producing really great work.