Indent Stores and Keelung Harbor: The Trendsetter of Cold War Taiwan

During the 1960s and 1970s, Keelung was famous for its indent store business, a trade that specializes in consigning goods for sale or purchasing imported goods. How should we understand the rise and fall of the "indent store" business in relation to the historical formation of Keelung city?

By Ho Yu-hong

Translated by Elizabeth Gardner

Edited by Sabrina Teng-io Chung

This article was co-published by StoryStudio and The National Archives Administration National Development Council and was translated and published with the permission of the original publishers.

With the current outbreak of COVID-19 worldwide, domestic tourism has become a viable option for those who cannot travel abroad. Keelung, a city less than an hour drive from Taipei, became a hotspot for domestic tourists of Taiwan. During weekends and holidays, the quiet and empty streets of the port city of Keelung will be filled with liveliness and fun.

A still and peaceful block on Xiao’er Street, Keelung City (Source: Photo taken by the author)

In the popular residential district of Xiao’er Street sits a block both quiet and tranquil. Strolling about these streets, a tourist would notice that the majority of stores lining the sides have their iron shutters locked tight. However, should one cast their gaze up, viewing the overhead canopies that perfectly cover the streets, it isn’t difficult to imagine these streets once full of life.

So drenched in the aura of the 1970s as though frozen in time, this block was once one of the most bustling places in all of Taiwan.

This block is known as the “Indent Store Street.”

THE ‘HIP’ NEW CITY THAT GREW FROM THE HARBOR

An industry now faded from the memory of most Taiwanese people, indent store was a trade that specializes in consigning goods for sale or purchasing imported goods. However, to further understand the burgeoning development of indent stores in the 1960s and 1970s, we must first direct attention to the historical formation of the city of “Ke-Lâng” (雞籠), the precedent of present-day Keelung.

Before the twentieth century, a group of people who hailed from Zhangzhou travelled north along the Taiwan coast from Bali, before settling on the land that would become Keelung. However, at the time, Keelung city proper was essentially a sandbank: its streets were barren, and its ground a soggy quagmire after rain. With the end of the Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Taiwan was ceded to Japan. To demonstrate their colonial and governmental capabilities, Japan’s Government-in-General of Taiwan resolved to transform Keelung, the port geographically closest to Japan, into a major modern deep-water wharf. A four-phase harbor construction project was launched thereafter. Targeting the previously cramped and marshy city proper, plans involving land expropriation and city reform were also carried out.

After a series of construction, the city--originally a sandbank formed from illuviated river deposits--was divided into “Greater Keelung”, a Han settlement based on southern coast of Keelung Harbor, and “Little Keelung”, the Japanese settlement sat on reclaimed land along the harbor’s eastern coast. Along with dredging and excavation projects, Keelung Harbor became both a city hub and a space for major business and trade.

After Keelung City became the most important harbor connecting Japan and Taiwan, in the 1930s, the construction of Baichimen Fishing Harbor bolstered the city’s fishing industry, and the building of a commercial port made Keelung capable of seaborne commerce. With this, local industry began to gradually shift its primary focus to commercial shipments. It would be no exaggeration to say that the thriving industry had transformed Keelung into the island’s most bustling city at the time. Amongst this urban jungle stood clothing shops offering all manner of styles, from wafuku (kimono) to yōfuku (Western apparel), watch shops selling the most fashionable udedokei (wristwatches), and kissaten (cafes) offering jokyū (maid) services. An array of products were shipped from Japan, catering to the needs of Japanese immigrants to Taiwan who desire many of the foods and daily comforts from their homeland.

Following the harbor opening in the 1860s, the Taiwanese people were more frequently exposed to imported goods. However, there were two reasons that truly allowed them to become accustomed to the purchasing and consumption of imported goods, including those from Japan. These include their everyday experiences under Japanese colonial rule and their reception of objects and commodities introduced from Japan.

THE FLOWERING OF POSTWAR INDENT STORES

The end of World War II brought about a peculiar sight in Takasago Park (高砂公園; roughly situated on Keelung Harbor South in the region now circled by Zhongsan Rd, Xiao’yi Rd and Zhongsi Rd) and the Kanziding area of Keelung. Many Japanese civilian repatriates (hikiagesha) would auction off the household goods and furniture they could not take home, hoping to earn a little cash. At the same time, the city also witnessed the arrival of a vast number of Nationalist government-affiliated military personnel and their family dependents coming to take over Taiwan from Japan. In 1949, the Nationalist government’s retreat from mainland China to Taiwan further precipitated an exodus of soldiers and civilians to Taiwan. With them, they introduced their home customs, such as diet, lifestyle, and dress, to postwar Taiwanese society.

A list of Japanese people repatriated back to their home country after the war, all from the two harbor cities of Kaohsiung and Keelung (Source: The National Archives Administration National Development Council)

In the early postwar era, the residents of Keelung would set up simple covered stalls by the harbour, selling new imports and second-hand goods brought by sailors. These imported or second-hand goods were sold through “black market trade”. The burgeoning development of indent stores with shop fronts began with the outbreak of the Korean War in the 1950s. U.S. sailors and soldiers stationed in Keelung Harbor brought with them masses of imported goods to be sold in the increasing numbers of indent stores, upscaling sales of these goods. Though Taiwan at the time was under a state of heightened political tension, Keelung’s economy thrived, allowing people to momentarily forget the immediate postwar turmoil.

A GOLDEN ERA OF INDENT STORES IN KEELUNG

In the 1960s, though Taiwan’s economy was gradually recovering, the Taiwanese people were still prohibited from leaving the island. Such travel prohibitions and the incessant demand for imported goods contributed to the thriving development of indent stores. The growing number of indent stores not only invigorated Keelung’s economy, Taiwanese people in pursuit of greater prospects in Keeling also led to the ballooning of the city’s population. In the Ren’ai District alone, where indent stores concentrated, the population doubled within the span of a decade.

With the outbreak of the Vietnam War in the 1960s, and the U.S. establishment of the “Rest and Recuperation” (R&R) Program, the Keelung Harbor saw the arrival of U.S. soldiers and U.S. navy ships docking for repairs. Keelung’s indent stores reached its golden age during this period.

A snapshot of the “Rest and Recuperation” Program, capturing the encounter of U.S. soldiers and a Taiwanese bar hostess in Keelung. (Source: The National Archives Administration National Development Council)

As mentioned above, the majority of postwar black market trade was conducted in the Takasago Park area of the Ren’ai District. During Japanese rule, this park was one of the most important recreational spots for the residents of Keelung city. Not only was it equipped with a pond for paddling and relaxation, it also contained the Zhupu Altar used both to celebrate the Ghost Festival and for concerts. However, aside from postwar repairs to the Zhupu Altar, the park’s original form had long disappeared due to wartime destruction and postwar immigrants’ temporary resettlement in the park.

During this golden era for Keelung’s indent store business, the city council decided to officially demolish Takasago Park to improve city appearance. New housing structures for residents of the surrounding area were built in the park’s place. The small hills that Takasago Park once occupied would be later referred to as the “Park Peak” area, where indent stores concentrated. Construction to accommodate the then expanding population likewise marked the origins of the aforementioned “indent store streets”. According to archival records, properties functioning as indent stores peaked at the number of two hundred at the time.

The small shop fronts of indent stores cannot be underestimated, for they hold some of the most popular selected items of the world. A photo depicting a Keelung indent store in 1968. (Source: National Archives Administration National Development Council)

Before the official ban on overseas travel was lifted in 1979, aside from studying overseas, visiting relatives, or conducting business, Taiwanese had no means of travelling abroad to buy overseas imports. In the 1950s, indent stores depended on imported goods sourced from U.S. troops and sailors. At the time, sailors would custom order windbreaker jackets made from jean fabric, a material that could carry heavier weights. These coats would have a further five or six pockets stitched into the back, where they could store more material, clothing, or other goods. In October 1960, many options for smuggling goods were shuttered, after the government announced the “Measures Against the Smuggling Activities of Merchant Shipowners and Seafarers” (商船船東及海員走私處分辦法) punishing merchants, shipowners, and sailors.

But such policies were met with countermeasures from those involved in the trade. Indent stores owners changed their methods for obtaining goods, developing the tactics of “collective smuggling” to help their sailor couriers. They would first use a secret signal to establish contact (such as both parties carrying matching halves of a cut dollar to covertly identify one another). The smuggled goods would then be packed into plastic waterproof bags, and at midnight, using the ‘bag-drop’ method, these bags would be dropped into the open ocean or harbor. Aided by fishing boats or sampan, they would perform the “release and catch” maneuver, hauling their “catch” onto the boat, before sailing to a designated pickup spot on the coast, where the goods would then be delivered to a set location by van. Another method involved having the smuggled goods flung into a controlled enclosed area for a dealer to intercept. Especially past harbor curfew, it wasn’t uncommon to see large gangs of bikes forming and swarming out of the harbor area. The majority of these smuggled goods would eventually make their way into intent stores for purchase.

At the height of indent store business, the harbor ran rife with smuggling. In 1960, it was required that whenever any sailors entered Taiwan transporting allocated goods, their captain would be required to compile a list of goods and make a customs declaration. Depicted is a document outlining the “Measures Against the Smuggling Activities of Merchant Shipowners and Seafarers” (Source: The National Archives Administration National Development Council)

Starting from the 1970s, the government allowed, under specific circumstances, prominent industry figures to conduct business overseas in the name of sourcing essentials such as equipment or materials or for establishing professional contacts. In addition, the Taiwan Provincial Importers and Exporters Association and the five major industry groups were allowed to apply for overseas travel in the name of “interview and observation”. Prominent figures in the “indent” industry and itinerant traders were willing to spend several thousand dollars on a trading license. They were also keen to directly join these aforementioned trade groups, opening new pathways for transporting goods into Taiwan. Those granted permission to travel overseas would sometimes engage in the “indent” business, carrying excessive quantities of imported goods into Taiwan. However, when entering Taiwan, they would inevitably face customs issues. To prevent their luggage from being confiscated or fined, they would often intentionally make a complete scene at the customs office.

KEELUNG CITY AS A DEPARTMENT STORE

Most of the imported goods flowing into Taiwan via sailor smuggling and itinerant traders ended up in indent stores.

The storefronts of indent stores were all rather small, customers would have to shimmy sideways to get in. But as the saying goes, “good things come in small packages”. Be it automobiles, coffins or living organs, whatever crosses your mind could be found in indent stores. From smaller items including the Little Nurse Mentholatum Ointment, chewing gum, chocolate, leather shoes, and imported wines, to larger items including phonographs, statues of the Buddha or Virgin Mary, nothing was too anomalous for indent stores to sell.

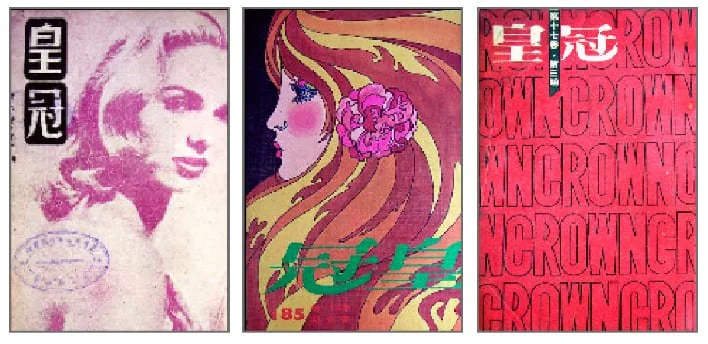

By displaying all manner of popular and trendy products for sale, indent stores essentially imported cultural knowledge from around the world into Taiwan which was then under martial law. For example, indent shop owners would exhaust all means to capture customer attention. Products on sale would be exhibited in transparent display cases. To a certain extent, this “window shopping” experience exposed the average Taiwanese customer to the “outside world” these imported goods embodied.

Moreover, indent stores differed from the traditional marketplace in terms of their spatial organization and display methods. In the traditional marketplace, products were displayed in rather disorganized manners, its space packed with crowds, and floorboards damp. By contrast, indent stores were relatively clean and well-lit, displaying an aura of “classiness” and modernity. Such an aura was further reinforced by the display of popular and trendy imported goods. After all, compared to local businesses, indent stores did not offer affordable pricing for products on sale.

To a certain extent, the open displays of indent stores exposed the ordinary people of Taiwan to imported goods and other marvels from around the world. Depicted is a photo of a Keelung indent store taken in 1968 (Source: The National Archives Administration National Development Council)

In the “warring period” between indent stores, shop owners developed a myriad of techniques to attract customer attention. Aside from display cases, shop owners sought to maintain a loyal customer base by engaging in casual chats and forging close relationships with customers. Doing so, they were able to gather information on the customers’ potential needs. For regular customers, they also promised to source specific goods when going on overseas trips. Shop owners’ individual charm and eye for products could also be counted as highly effective tactics for maintaining business.

However, with overseas travel made available in 1979, indent stores were no longer the only channel by which the people of Taiwan obtained overseas goods. Once customs tariffs were lowered, and masses of clothing and medication were imported, the usage and consumption of products from indent stores were no longer symbols of social status.

The 1980s saw the rapid growth of large department stores and convenience stores. Despite their specialization in catering to customer needs, indent stores still couldn’t compete with the new changes and went out of business one by one. The once thriving and bustling indent shopping district gradually faded into obscurity.

An indent store street in Keelung today (Source: Photo provided by the author)

However, the demise of indent stores does not signal an end to Taiwanese people’s practice of buying goods to sell in Taiwan while on overseas trips. This practice becomes even more prevalent with the rise of online shopping, challenging the shop owner’s eye for trendy goods.

INDENT SHOPPING DISTRICT: A RETURN TO TRENDINESS

As the saying goes, “success and failure lie in the same root cause”. At its height in the 1980s, Keelung Harbor had risen to become the world’s seventh largest cargo port. But due to domestic restrictions, Keelung’s new harbor plans did not materialize, and Taipei Harbor, initially constructed to support Keelung Harbor’s functionalities, would gradually take over its place. Furthermore, since mainland China’s economic reform and opening-up, Keelung Harbor’s cargo-handling capacity would steadily decline. For numerous reasons, the two main arteries that had kept the heart of Keelung beating--its indent shopping district and harbor trade--had been cut off. Once a bustling city, Keelung had devolved into a silent harbor city deserted by a majority of its residents.

In recent years, with the rising popularity of international cruises and domestic travel, along with the return of youths to their home in Keelung, the harbor city has entered a new stage of revival. New signs of liveliness could be found in the once flourishing indent shopping scene. In the “Park Peak” area, these homecoming youths have been hosting fairs and opening small specialty shops or izakaya, restoring life to these long-neglected streets. Even though business no longer runs on indent stores, these small storefronts still flow with the life and vitality of the locals, giving visiting tourists from around the world a taste of Keelung’s beauty and history. The Keelung indent shopping district seems to have gradually returned to trendiness.