Captured by War, Lost before Liberation: Taiwanese in World War II Internment Camps

During WWII, there were hundreds of Taiwanese living in Southeast Asia. They were regarded Japanese, lost everything overnight and were detained in internment camps. Dr. Shu-min Chung had dug up historical materials in search of the Taiwanese in internment camps, trying to fill in the forgotten history of overseas Taiwanese.

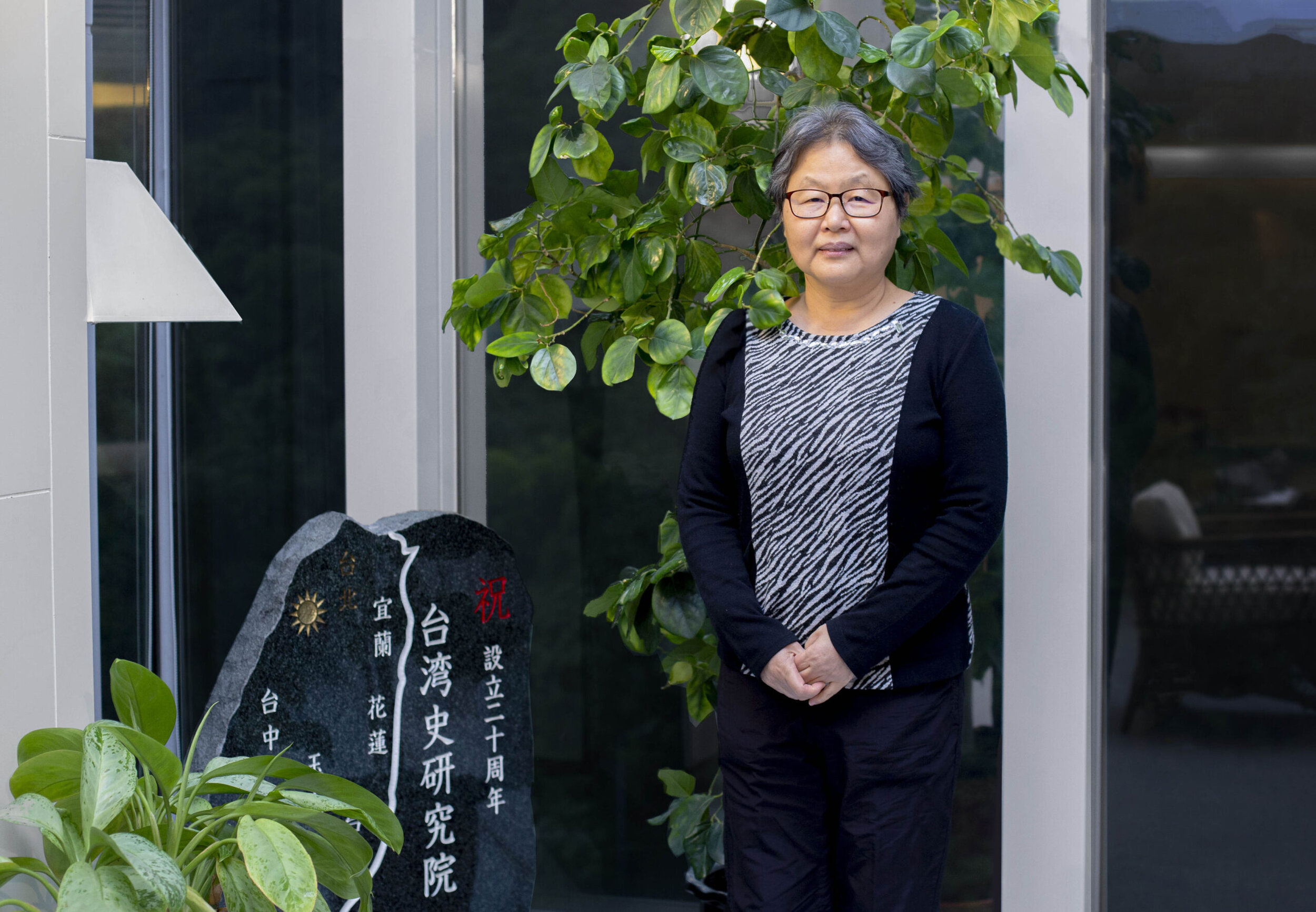

Dr. Shu-min Chung (鍾淑敏) is research fellow of Taiwanese history at the Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica. Dr. Chung received her Ph.D. at the University of Tokyo and specializes in the history of Japanese colonialism, immigration, and overseas Taiwanese in early twentieth century China and Southeast Asia. Her recent book titled 日治時期在南洋的台灣人 (Taiwanese in Southeast Asia, 1895-1945. Taipei: ITH, Academia Sinica, 2020) explores the stories of Taiwanese immigrants in Southeast Asia under the context of Japan’s imperialist expansion in the area. Dr. Chung also offers courses at several institutes, including National Taiwan University, National Chengchi University, and National Taiwan Normal University.

By Shu-min Chung (鍾淑敏)

Interviewed by Yi-Shan Wu (吳易珊) and Chih-Yin Liu (劉芝吟)

Translated by Grace Ho Lan Chong

Edited by Yu-Han Huang and Sabrina Chung

This piece first appeared in Research For You and was translated and published with the permission of the publisher.

THE FORGOTTEN HISTORY OF TAIWANESE DURING WORLD WAR II

When discussing wartime internment camps, most people might recall the British and American civilians detained in Japanese internment camps in the movie Empire of the Sun. Few people are aware that during World War II, there were hundreds of Taiwanese living in Southeast Asia. They were regarded Japanese, lost everything overnight and were detained in internment camps. Research For You (研之有物) interviewed research fellow Shu-min Chung (鍾淑敏) from the Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica. She had dug up internment camps notes, newspapers, and other historical materials in search of the Taiwanese in internment camps, trying to fill in the forgotten history of overseas Taiwanese.

1941: TAIWANESE UNDER MASS ARREST ON THE MALAY PENINSULA

In 1941, the European theatre of World War II was stuck in a locked state. On December 8, a drastic change erupted in the Pacific theater. Japan suddenly launched lightning raids, sending troops to Pearl Harbor, the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia, the Philippines, and other places. The Pacific Ocean was covered in smoke.

At that time, many Southeast Asian countries were colonies of Western countries, including Burma, India, the Malay Peninsula, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia), the French colony of Indochina (present day Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos), and the US controlled Philippines. To prevent espionage, both sides of the war immediately launched detention operations, arbitrarily arresting “enemy aliens.”

On December 8, a round of mass arrest took place on the Malay Peninsula, all local Japanese were summoned to the police station. At that point, no one was certain of their fate: one moment, it could be the whistling of artillery, another, just the sound of the wind. A few days later, some Japanese were sent to the Johor Bahru prison, and some were sent to St. John’s Island, including many Taiwanese in Nanyang.

During World War II, both sides of conflict set up internment camps to detain the enemy’s people. Japanese troops in Japan and China detained British and American civilians; the United States also imprisoned approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans. The picture shows Japanese school children in an internment camp in the United States. In response to the Japanese American Redress Movement, the postwar US government issued an apology and offered reparation to those interned.

Photo | U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia

TAIWANESE ADVANCING IN NANYANG: THE FOREMAN, THE PHYSICIAN, AND THE ENTERTAINER

The flames of war arrived suddenly, and civilians are always the first victims. But why were there so many Taiwanese living in Burma, Indonesia, and the Malay Peninsula at the time? Why did these Taiwanese travel all the way to Nanyang during Japanese rule?

Because wherever there is opportunity, there one should follow. Just as many of the younger generation of Taiwanese are actively seeking overseas experiences these days, Nanyang was also the dream path for Taiwanese under Japanese rule. For better treatment and development opportunities, many Taiwanese went to Singapore and the Malay Peninsula, especially Indonesia.

At home, the status of “Taiwanese” was inferior to that of “Japanese.” When they arrived in Indonesia, however, they held the same status as Japanese natives. Particularly after the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), Japanese and Westerners were on equal footing. “Taiwan sekimin” (臺灣籍民, the general term for the registered Taiwanese who arrived in China and Southeast Asia during the Japanese Occupation) were treated better than those from Qing China. [1] This attracted many people there to start trade and businesses, dealing in tea, agriculture and forestry specialties, and groceries.

In Singapore and Malaysia, the Taiwanese were roughly divided into three categories.

The first is those employed by Japanese mining and rubber companies. Japanese companies employed a large number of Chinese coolies and thus required middle men who were proficient in both Chinese and Japanese. Hence, the Taiwanese stood out as foremen and supervisors.

The second category is medical school graduates. They were in Nanyang to start their own clinics and advance their medical careers by treating the local Chinese.

The third category of Taiwanese citizens is special: the entertainers. As there were a large number of Chinese workers in Nanyang in the 19th to 20th century, in addition to making a living, a life of entertainment also developed amongst the common people. Many theatrical companies, performers, and Taiwanese opera troupes took advantage of the market to perform around Nanyang.

Generally speaking, relative to Chinese laborers and coolies, Taiwan sekimin enjoyed a higher social status and living standards. Some chose to settle and others traveled between Nanyang and Taiwan. According to the statistics from the Government-General of Taiwan, although the majority case was those going between China and Taiwan, there were about 3,000 people settled in Nanyang.

Most Taiwanese detained in India worked as an entertainer, but among the detainees, there were also many merchants, small business owners, some doctors, drug dealers, and foremen of Japanese companies.

Figure | Research For You, iStock (Source | Shu-min Chung)

ORPHANS IN ASIA: TAIWANESE? JAPANESE? FUJIANESE?

To work hard for their life, Taiwanese people had to advance step by step to survive in a foreign land.

As “orphans of Asia,” the Taiwanese seemed to have no choice but to bear ambiguous and complicated identities. Nanyang was a land of diverse nationalities, thus resulting in the Taiwanese’ utilization of code-switching and adoption of different identities for different situations. If anti-Chinese conflicts broke out in the area, their Japanese identity provided a net of protection; when in the overseas Chinese district, the Taiwanese hid their nationality, communicating and conducting business as Fujianese Chinese.

However, when a ruthless war broke out, there was no room for identity negotiation. All Taiwanese were marked as Japanese and taken to camps.

This particular history of World War II has rarely been dug up and explored, and even if Japanese scholars devoted themselves to research after the war, they did not mention the Taiwanese. Shu-Min Chung, a research fellow at the Academia Sinica, collected historical materials and searched for the parties involved in internment camps, including the Taiwanese from Singapore and Malaysia who were shipped off to India, and those from Indonesia who were sent to Australia.

Among her findings, two key pieces of evidence provided important clues.

One comes from Hiroshi Kobayashi, a technician of the Japanese company “Sango konsu” (三五公司). Using letters the size of the head of a match, he wrote 8 notebooks in the dark. With the assistance of Kiyoshi Honma, a Japanese dentist, he sealed the envelope with a teeth mold and smuggled it out of the camp secretly. The roster of detainees produced by Hiroshi Kobayashi, recordings of names, places of arrest, and residences in Taiwan, has become key historical material for studying the Taiwanese in internment camps.

The other important piece of information is the newspaper Indowara Correspondence (インドワラ通信). Published in 1966, the newspaper released the recollections of Taiwanese and Japanese detainees.

TAKEN IN THE NIGHT: DETAINED IN INDIA AND AUSTRALIA

Shu-min Chung’s research discovered that there were two main internment camps where the Nanyang Japanese were imprisoned.

The Japanese and Taiwanese from the Malay Peninsula were sent to India. Those from Indonesia, Borneo and other places were taken to Australia. Overnight, these people lost all their possessions and were taken onto ships with no idea where they were headed, leaving their fate uncertain. Most people were unable to leave these camps until mid 1946.

During the journey, under the watch of patrolling soldiers with guns, large numbers of Japanese detainees were forced to squeeze into the cabin of extremely hot ships with no food for over 3 days, then transferring to Delhi, India for detention. In the tent-camp of Purana Qila, India, due to poor sanitation and lack of clean water, malaria, red diarrhea, and typhoid fever were extreme threats. The local temperature in the day was extremely hot, but dropping at night. Most prisoners were detained in a hurry, thus lacking proper, warm clothing. Many frail people were unable to sustain themselves, losing their soul in a foreign land.

Among the over 2,000 prisoners, 182 were Taiwanese who were arrested in Singapore and Malaysia.

“Due to colonial relations, these Taiwanese were categorized as Japanese and unfortunately ended up as prisoners.”

BREAKING DAWN: A SELF-SUFFICIENT AND SELF-GOVERNING COMMUNITY

In 1943, Taiwanese detainees saw a change in their suffering.

The detainees were sent, one after another, to the oasis city of Deoli, leaving behind their crude tents to move into brick houses. These new shelters were equipped with kitchens, baths, sports fields, and complete sanitation and medical equipment. The detainees were arranged in different quarters according to small families, large families, single women, and single men.

The Japanese and Taiwanese arrested in British Malaya (including current Malaysia and Singapore), were finally sent to India, moving into the internment camp in Deoli.

Figure | Research For You

Aside from the restrictions on the freedom to go out, life in the shelter was almost like a self-governing small community.

Each day after morning and evening roll calls from the supervisors, detainees had the rest of their time for personal activities, such as planting vegetables and tailoring. The shelter did not perform forced labor. Stuck in the camp with no hope for freedom, detainees organized their own cooking classes, gardening club, held sumo tournaments, played movies, or played tennis to prevent the life of imprisonment from becoming hopeless.

Work and rest were easy to sort out, but the taste of home was hard to give up. Detainees learned to pair their rations with beans, transforming the ingredients into miso and tofu that Japanese are accustomed to. Detainees held in Australia faced a greater challenge. They had to switch from Taiwanese and Japanese cuisines to eating beef and cheese. But in any case, having at least two meals a day during wartime was already a huge blessing.

“BECOMING JAPANESE”: CHILDREN IN INTERNMENT CAMPS

Half a century later, most of the Taiwanese who were interned have passed away. But most of the interviewees had been sent in with their families as children. Their experiences allowed Shu-min Chung to collect memories of the internment camp from the perspective of childhood.

Post-war films and memoirs in the West often describe the tragic experiences of abuse that Allied prisoners of war suffered in Japanese internment camps. Compared to those sites, the British internment camps were quite humane in terms of their modernized carceral practices. Interviewees who grew up in those camps recalled there being groceries and relief supplies; Indian camps distribute petty cash every month, sponsored by the Japanese government; and the Australian internment camp even provided a mail-order catalog. [2]

The children didn’t fully understand how chaotic things were at the time. They were eating well, sleeping warmly, and living with their entire family. They did not seem to have undergone a lot of wartime trauma. The internment camp was like a super large air-raid shelter, indirectly blocking the fiery conflict outside.

However, the Allied forces would win a round, then the Japanese would attack a city, and no one knew when the war would finally end. The children’s education became another problem, so the detainees organized their own schools inside the internment camps with hand-written textbooks, opened primary schools, and taught their own children.

“Unexpectedly, this period of life in the internment camp allowed the Taiwanese to learn to ‘become a real Japanese.’”

The second and third generation Taiwanese immigrants in Nanyang had almost no exposure to Japanese culture. But in the internment camps in India, their children wrote in Japanese, sang school anthems praising the spirit of yamato damashii, worshiped the imperial palace, and celebrated Japanese festivals. Incidentally, they ended up experiencing the process of “imperial subjectification” (皇民化).

The No. 1 Primary School of the Deoli Asylum had 8 levels. The student calendar was the same as that in the Japanese mainland. They also learned the school song that emphasized “loyalty to the emperor and patriotism,” and “the spirit of yamato damashii.”

Picture | Painted by Mine Kazuo, from Centre for Documentation & Area-Transcultural Studies, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies/21st Century COE Program eds., Painting Collections of Mine Kazuo.

Radio gymnastics class. The children in the shelter cleaned the classroom at 7:15am, morning meeting at 7:30, gymnastics before 7:45, then had class until 4pm.

Picture│ Edited by Kimura Jiro, Sketch Recollections on Internment Experiences in India: 1941.12.8-1946.5.19 (Printed Paper Collection), without page number, picture 131.

SURVIVED THE WAR, BUT DIED ON THE EVE OF FREEDOM

The internment camps seemed to enjoy a period of relative peace for 5 years, avoiding direct lines of conflict; but the unpredictable god of death unexpectedly arrived at war’s end.

On August 15, 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Powers. The detainees in the internment camps in India did not receive the news concomitantly. Despite having received official notifications of Japan’s surrender from various countries, many Japanese refused to believe it. “This is absolutely fake news!” They doubted the authenticity of broadcast and newspaper sources, even claiming that the Japanese envoy who paid a visit to explain was a fake.

The extremely polarizing atmosphere split the detainees into two groups: one believing in Japan’s victory, another accepting their country’s defeat. These two groups were in constant conflict. Those in the “Victory Group” began violently sanctioning “those who did not believe in the country” and attacking guards. The situation increasingly worsened, triggering the 226 Incident as a result. The Indian government fired at the internment camps, resulting in 17 casualties.

After years of war, lives of detainees were lost on the eve of freedom. Perhaps, this tragedy became unavoidable because of the life of uncertainty, anxiety, and isolation of the detainees, even when the internment camps seemed far removed from the war.

Qiu Yun-Lei (邱雲磊), a professor of the National Taiwan University’s Department of Electrical Engineering (young child in the picture), was sent to an Indian internment camp together with his parents who ran an iron ore company in Singapore. He recalled that his home in Nanyang was frequented mostly by Malays and Indians. He didn’t start to learn Japanese until he entered the internment camp.

Picture | provided by Qiu Yun-Lei

SMALL PLAYERS STEAMROLLED BY GRAND HISTORY

Some people died in detention, others were killed in internment camps. But for the Taiwanese who survived the war, where did they settle in the aftermath?

Shu-min Chung mentioned that after the Selai Temple Incident (余清芳事件), the family of one of the interviewees hated the Japanese regime and moved to Indonesia to make a living. Later, the family was sent to an Australian internment camp. The parents only permitted the children to read Chinese and English, refusing to let them take Japanese courses. When war ended, they became worried about being sent back to Japan, refusing repatriation. Eventually, they were forced to board the ship by Australian soldiers but were relieved when they landed in Taiwan.

This type of panic and fear reflects the helplessness of the Taiwanese in this great age.

After World War II, Taiwan had once again become an “international orphan,” no longer belonging to Japan. The Allied forces did not recognize that the Nationalist Government had immediate jurisdiction over Taiwan, while most Taiwanese were being repatriated to Taiwan. However, a majority of them had already settled down in Nanyang for several generations and thus had no choice but to become separated from their local relatives. Despite enduring all the hardships of war, they lost the homes and businesses that they had worked hard to build.

“The identity of the Taiwanese has always been a bit ambivalent, as they have never been able to choose for themselves.”

Shu-min Chung, who has spent many years studying the World War II history of Taiwan, has arrived at a few realizations.

Taiwan sekimin often oscillated between Japan and China based on personal benefits, but in fact, the situation was constantly influenced by the overall global situation.

This realization motivated Shu-min Chung’s ongoing research. The overseas history of Taiwanese under Japanese colonial rule is often ignored. On the one hand, Taiwanese seldom kept a record about themselves, leaving very little information. This period has also been deemed political taboo, a notion generated during the transition of ruling regimes and resulting in the erasure of information. Elders avoided sharing their own stories, leaving their children and grandchildren with no way of understanding the family history.

This is precisely why historical research matters. Otherwise, there will be a lack of Taiwan-centered historiographical perspective to the study of wartime Taiwanese history.

“Our family’s history is Taiwan’s history, and a part of this era’s history.”

Shu-min Chung said sincerely: “I hope to address this lacuna through research, but even more so, I am looking forward to Taiwanese people retrieving their own history. As long as you are willing to record and narrate your family story, you can help fill in Taiwan’s lost history for the future.

Although historical materials are hard to find, following neglected and forgotten history and telling the stories of the Taiwanese has been a concern of Shu-min Chung’s investment in historical research. She is also studying Taiwanese prisoners of war and war criminals during World War II, hoping to shed light to the underrepresented histories of Taiwan.

Picture | Research For You

Footnote:

[1] Taiwan sekimin is a status that signifies colonized Taiwanese residents, who were identified as Japanese nationals, in China and Southeast Asia. Along with its victory in the Sino-Japanese War (1895) and legal system reforms in the late nineteenth century, Japan successfully abolished the “unequal treaties” with Western nations and extraterritoriality recognized in those treaties; Japanese nationals, including Japan’s Taiwanese and Korean colonized subjects, thus enjoyed a relatively more privileged status than Chinese nationals in China and foreign countries. The status of Taiwan sekimin reflects the tricky relationships between Taiwanese and other groups of Chinese: although they were seemingly similar in cultural, linguistic, and ethnic perspectives, Taiwanese enjoyed the protection of the Japanese Empire. On the other hand, Taiwan sekimin also reveals the fact that Taiwanese were distinguished from Japanese natives under Japanese colonialism, although they were legally Japanese.

[2] After the war, in 1946, the Singapore-based newspaper Nanyang Siang Pau (南洋商報) also mentioned: “Each month a petty cash of 16 rupee was distributed--12 rupee was sponsored by the Japanese government, while 4 rupee by the British.”