What TikTok Can Tell Us About Indonesian Migrant Worker Affairs In Taiwan

In our second feature for the 2020 Big Ideas Competition: Exploring Global Taiwan series, award recipient Pranav Dayanand makes a case for what TikTok can tell us about the complex state of Indonesian migrant worker affairs in a rapidly-changing Taiwan.

By Pranav Dayanand

Featuring work from Jielun Zheng, Kana Minju Bak, Angelah Liu

Edited by Elizabeth Shaw and Sabrina Chung

Photo by Rio Lecatompessy on Unsplash

Over the summer, my peers and I worked on a research project that aimed to gain a more nuanced view of the experience of Indonesian migrant workers in Taiwan and the roles they hold in society.

Indonesian migrant workers have consistently been a mainstay in the domestic news cycle in Taiwan as incoming migrant workers continue to test positive for COVID-19 since massive outbreaks occurred in the community in November 2020. Despite the mandatory 14-day quarantine period for all incoming migrants, there have been a rising number of confirmed cases among the Indonesian worker population. In response, the Taiwanese government instituted a ban on all Indonesian migrant workers on December 4th, 2020.

Many of these developments came during a time of increased tension between migrant worker groups and their Taiwanese employers. Since 2019, there have been several protests organized by the Migrant Empowerment Network in Taiwan (MENT) that have attempted to galvanize support for what they perceive as unjust labour practices. Before the coronavirus truly began to ravage the global community, some fellow students and I at the University of Toronto submitted a proposal to the 2020 Exploring Global Taiwan competition to fund a research project. Having read extensively about the struggles faced by foreign domestic workers in South Korea and Singapore, we were keen on observing the migrant worker experience in Taiwan, often seen as one of the more socially progressive countries in the East Asian region due to its recent legal amendment to national marriage law that gave same-sex couples the right to marry. Our initial goal was to shoot a documentary film and interview local Taiwanese students and Indonesian domestic workers to gain various perspectives.

As luck would have it, international travel became increasingly difficult and we were forced to reassess our research methods. Initially, we began by examining some of the pre-existing research on the topic from experts such as Pei-chia Lan, Stephen Lin, and Anne Loveband. Aaron Wytze Wilson, a fellow University of Toronto researcher and co-founder of The Taiwan Gazette informed our group of the presence of Indonesian migrant workers in Taiwan on the Chinese TikTok app. These migrant workers often post videos of their daily lives and experiences while living and working in Taiwan. By virtue of his suggestion, we were able to find many Indonesian TikTok users and used their short video clips as a guideline into the Indonesian migrant worker experience. Although most of the videos revolved around Indonesian dance trends, they still allowed us some insight into their daily lives and employment situations. Furthermore, we contacted some college students on Taiwanese campuses and were able to distribute a survey to properly examine the domestic view of Taiwan’s college-educated youth population as well.

Until 1992, when the Employment Services Act guaranteed a change in immigration laws and sociocultural circumstances, most domestic care work was conducted by female members of the family in Taiwan. Even as of 2009, 67% of those over the age of 65 were cared for by their younger female family members. However, as the 1950s ushered in a new economic age of rapid industrial development, women began to enter the workforce in vast numbers that impacted their capacity to perform their domestic care work. Unlike the West, Taiwanese families appear to be weary of nursing homes and it was often difficult to hire local caregivers, hence the influx of migrant workers to fill these roles.

According to Anne Loveband, nearly 70% of these workers were women and are often forced to work 14-18-hour days, often at the behest of their employer. The employees were almost never employed directly since the Taiwanese government allows brokerage agencies to recruit them in their home countries. Since migrant workers are not subject to Taiwanese labour law, it is not uncommon for these employment recruitment agencies to be exploitative. They have often charged exorbitant rates for their services and many migrant workers are faced with being forever indebted to the agencies.

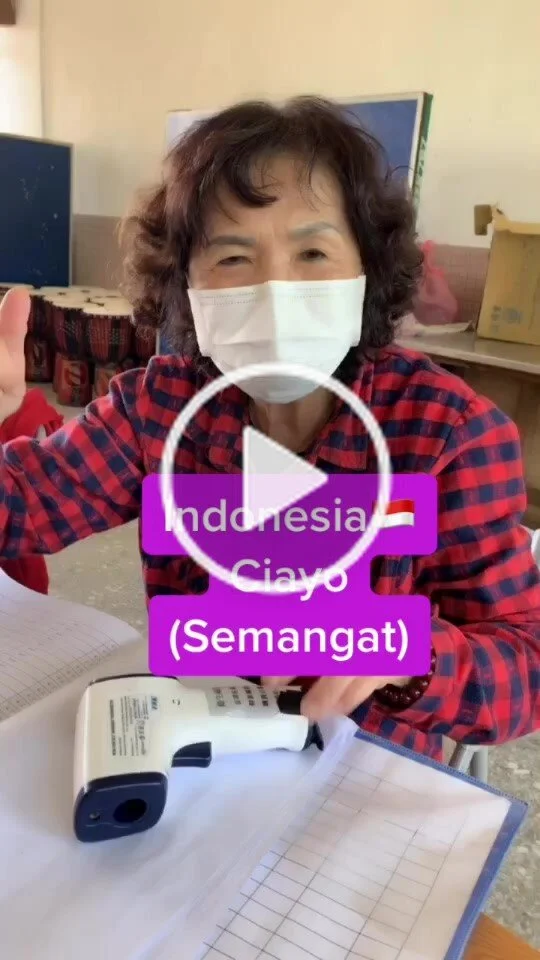

In many ways, both our research with TikTok and our survey findings appeared to affirm many of these claims, but not in the ways we expected. In terms of TikTok, we examined a variety of accounts wherein young women documented their daily lives as domestic care workers. Their interactions with the elderly folk they care for appear pleasant, and it was not uncommon for them to repeatedly star in their short video clips. Many videos showed migrant workers teaching them Indonesian phrases and making them small Indonesian flags, showing a degree of cultural exchange that frankly was not expected. In terms of their outlook on Taiwanese society, one user named @umieulien_08 made a video exclaiming that local Taiwanese people oftentimes were more friendly to her than the other local Indonesians they met in Taiwan. In fact, some other videos even show pleasant interactions between Taiwanese domestic workers and their families, celebrating birthdays and holidays together.

However, other videos detailed a darker side of migrant worker experiences with the brokerage agencies and their employment structures. Many of the videos lamented the lack of holiday benefits they have in Taiwan. In the comments, it is relatively common for the only advice to be to ‘ask your agency for a different placement’. These workers were in fact beholden to a brokerage agency and required their involvement to broker any sort of change in their current employment situation.

In order to understand the perspectives of Taiwanese youth, we created a google docs survey and asked some of our contacts in Taiwan to distribute the survey to their peers at their local university. A total of 52 students aged 18-15 received the survey and the responses carried a range of perspectives. Generally, most Taiwanese respondents had little opinion on Indonesian migrant workers. Most viewed them as either friendly or hardworking, even if they had not been in contact with any before, and all supported their presence in Taiwan; but were almost universally against a path to citizenship.

However, one response seemed to echo a common sentiment that seemed to encapsulate the issue of domestic workers as a whole; that they perform various jobs (ex. manual labour, domestic care) that Taiwanese people would never do.

In short, as the situation for migrant workers became more fraught with tension mounting from protest movements and the uncertainty of COVID-19, our research showed their experience in Taiwan is often more complex and nuanced than we initially thought. While the domestic workers often feel welcomed by the elderly they care for and wider Taiwanese society, they are not included under many domestic labour protection laws such as the Labour Standards Act, which continues to put them in a position of precarity. Our hope is that through our research into their online presence we were able to provide some added insight into their lives and create a more active dialogue between government officials, Taiwanese citizens, and foreign domestic workers.

Bibliography

Hioe, Brian. “Migrant Workers Hold Rally and March, Calling for End to Broker System”, New Bloom, December 8th, 2019.

Lin, Stephen, and Danièle Bélanger. "Negotiating the Social Family: Migrant Live-in Elder Care-workers in Taiwan." Asian Journal of Social Science 40, no. 3 (2012): 295-320.

Loveband, Anne. "Positioning the Product: Indonesian Migrant Women Workers in Taiwan." In Transnational Migration and Work in Asia, 89-103. London: Routledge, 2006.