Meet Boss Evan -the man behind Taiwan's zombie content farms

A mysterious figure from China, “Boss Evan” has trained dozens of online fraudsters and propaganda peddlers. Now, he’s created an entire platform for anyone to bootstrap their own content farm empire.

By Jason Liu (劉致昕), Ko Hao-hsiang (柯皓翔) and Hsu Chia-yu (許家瑜)

Photography by Su Wei-ming (蘇威銘)

Design by Brittany Myburgh

Translation by Harrison Chen

This piece first appeared in The Reporter (報導者) and is published under a creative commons license.

In part one of this series, we met some of the uncles and aunties who fall prey to health scams and Chinese propaganda on messaging app LINE, as well as the fact-checking organizations looking to hinder the flaw of fake news. In part two, we learned about Malaysian content farm operator Yee Kok Wai, whose “Global Chinese Alliance” series of websites pump out pro-unification content that makes its way to LINE and Facebook. In part three, we meet the shadowy figure who provides easy-to-use web tools for anyone to set up their own content farm.

IN A TELEGRAM GROUP OF 481 PEOPLE, WE FIND “THE BOSS” OF THE CONTENT FARM EMPIRE

“Are there any pros here who know where I can buy Facebook accounts?”

“Member #5450 asks: my click rate has suddenly stopped growing, and friends can confirm that when they visit the counter doesn’t increase.”

“If you work hard, you’ll be buying a mansion in no time.”

On the encrypted messaging app Telegram, there is lively discussion in a group called Big Durian (大榴蓮群). The group has 481 members using a mix of both simplified and traditional characters. Payment can be received via WeChat, Alipay, Paypal, Bank of Singapore, amongst other methods. The members of the group are all content farm operators, and they run their content on platforms such as Qiqu News (奇趣網), KanWatch, beeper.live, and Flashword Alliance (閃文聯盟).

Flashword Alliance is owned by “Boss Evan,” an elusive figure who provides counsel and platform technology to novice content mill operators. Instead of the traditional model for content farms where content creators and platform owners share the profit, Flashword Alliance lets creators pay a monthly fee of $30 USD to set up their own website, independently manage traffic, and pick up ad placements. The platform also provides customer service at $6 USD a pop, giving users step-by-step guidance on how to rake in revenue.

Flashword Alliance, a separate service outside of Boss Evan’s content farms, allows people to pay $30 a month to have their own web site, rather than the usual cooperative profit-sharing model for content farms. Source: Flashword Alliance website page

In other words, spammers like Yee Kok Wai (余國威) of Malaysia, who we introduced in part two of the series, can single-handedly set up a dozen pro-unification content farms (the Global Chinese Alliance series of pages), and manage the entire operation by himself.

WEBSITES THAT POP UP AND THEN TAKEN DOWN

If you search online for Big Durian or Flashword Alliance, you will find instructional videos and blog posts on how to “make tens of thousands a month” and “walk the road to money making.”

The earliest post is from 2015, when users taught each other how to make money via content farms. In the comments section of a Big Durian instructional video on YouTube, users share invitation links and referral codes, as well as a recent post saying Big Durian has switched to a new domain -- Jintian Toutiao (今天頭條). We can deduce from the video that these “businessmen” have been running content farms for at least four years.

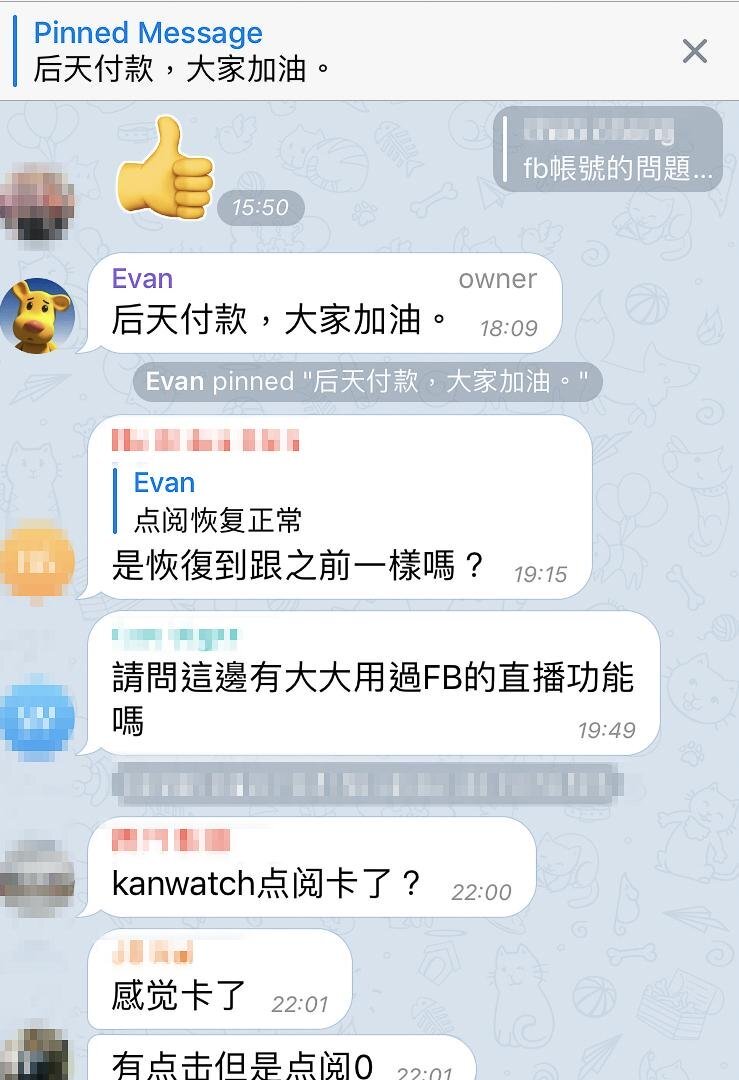

We quietly observed the Big Durian group and saw questions ranging from the definition of “content farm,” to how to buy fake accounts, to how to transfer funds. Someone named Evan — who users called “the boss” — gave answers. With his "daliulian" Telegram account, Boss Evan would links to the latest incarnations of the platform, the times when profits would be distributed, and tips on how to make more money, such as: “pay day is tomorrow, everyone work hard” or “buy a 100,000 follower fan page and then make a post there. Clicks come fast.”

We found Boss Evan's personal Facebook profile from a screenshot explaining how the content farm works. Aside from a few pictures of cartoons and dogs, he only had a QR code to connect with him on WeChat and a photo of a man he claims is a swindler.

Next to the WeChat invitation he wrote a rare message:

“I invite you to participate in Flashword Alliance: http://www.orgs.pub/, members receive payments directly from Facebook; you get money for clicks, it’s self-explanatory, you’ll get every penny.”

Boss Evan wrote in 2018 that user clicks from Hong Kong, the US, Australia and Canada would lead to larger amounts of revenue, about $10 USD per thousand clicks. Clicks from Taiwan were valued at $4 USD per thousand, and clicks from Malaysia at $2 USD per thousand. We attempted to contact Evan on various platforms but did not receive a response.

(Update: After the article was published, Evan reached out to The Reporter to discuss his views on content farms, which have been added to the end of the article.)

We found Boss Evan’s e-mail address through a Facebook page associated with beeper.live, and finally got a glimpse of his domain of operations.

THE “BOSS” WHO OPERATES AT LEAST 399 WEBSITES IN FOUR COUNTRIES

We searched for Boss Evan’s email on Website Informer and DomainBigData and found different addresses under the name of Evan Lee. We then used those addresses to trace his steps through markets he had established in various domains. For example, using Evan’s name and the same Google Analytics tracking ID, we found that Shicheng (獅城網), Singapore's largest free online bulletin board, is registered in his name. We also discovered he once purchased a Facebook fan page with 50,000 followers. He's also developed a multi-country news aggregator app, and even an online currency exchange website.

We did a search using Evan’s email on Website Informer and found other associated emails, which allowed us to pull back the curtain on his business operations. Source: Website Informer webpage screenshot

Using his associated emails, we found that aside from the Google Analytics ID UA-19409266, he also owned the ID UA-59929351. From these two IDs, we found that Evan’s business empire included at least 399 different websites.

Amongst these 399 websites, all of them were content farms producing a variety of different types of content, covering the Singapore, Taiwan, China, Malaysia and Hong Kong markets. Some contained gossip from Hong Kong universities, dramas that Chinese parents liked to watch, or pet memes. There was also content touching on Malaysian, Taiwanese, Hong Kong and Chinese politics. Content on China was largely positive, and adopted a “greater China” ideology. There were also websites about weather and employment in Singapore, exchange rate calculators, and erotic websites.

With a rich experience in running content farms, Boss Evan offers advice to members of the Telegram group who are anxious about not making money, offering suggestions on how to increase traffic. He uses his payment messages as encouragement, posting screenshots to members to show that good articles can get more than 300,000 views, earning about 1,200 Singapore dollars or $900 USD (assuming a payment of 4 Singapore dollars per thousand clicks).

GROUP HUDDLES ON GETTING AROUND THE FACEBOOK BAN

On Christmas morning 2019, Boss Evan dressed up as Santa Claus and notified the group that he had issued payments. Aside from thanking the boss, the members asked if their Facebook “reach rate” had recovered. “Not yet,” Evan replied.

Chen I-Ju (陳奕儒), Facebook's public policy manager in Taiwan, said the company “algorithmically suppresses” websites with “poor user experience,” resulting in lower reach rates.

But the group came up with solutions to get around this. Take user @ink99 as an example:

A fan page of theirs with 60,000 followers reached a new record of 140,000 hits. User @ink99 suggested that posts should be written with positive language in order to avoid being reported. Another user Yu2 echoed this advice, attributing his page’s 40,000 hits to Facebook recommending his links, while others shared strategies such as rotating their accounts and avoiding spam.

According to Chen I-Ju, Facebook monitors activities on the platform and continues to update its community guidelines to reduce the number of fake accounts. But from our observations on the Big Durian group chat, it doesn’t matter whether it’s Facebook or Google Adsense, these users can come up with solutions on how to work around new guidelines.

Recently, Boss Evan changed the rules on his platform so that political articles were no longer allowed, possibly to avoid sensitive topics arising from recent events between China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, but also because such messages have become focal points for detecting disinformation on many platforms. Even so, Boss Evan cannot distance himself from politics.

In addition to Malaysian content farm operator Yee Kok Wai, there is another notorious figure in the Big Durian chat group — a user named “Ghost Island” (鬼島), whose profile picture features an image of the infamous Taiwanese content farm website Ghost Island Mad News (鬼島狂新聞).

Journalists at The Reporter examined the Google Analytics ID behind Ghost Island Mad News, and realized that it was the same as Yee Kok Wai and the Qiqi content farms: UA-19409266(-3). Ghost Island Mad News uses two additional domains, taiwan-madnews.com and ghostislandmadnews.com, both registered under the same email address — joXXXXXX@yahoo.com.tw. We found the owner of said email address, an individual named A-hua (阿華, pseudonym). Over the phone, A-hua told us that he lives in Kaohsiung.

THE KAOSHIUNG MAN BEHIND GHOST ISLAND MAD NEWS

“That’s right, that was me in Big Durian.” A-hua tells us that Big Durian moderator, Boss Evan, is a Chinese citizen living in Malaysia, and that he runs the platform to help people make advertising money from Google and Facebook. Today, the platform forbids political content, very likely due to an article that A-hua had written a month or two ago.

All Taiwanese know about Ghost Island Mad News, run by Big Durian Group member A-hua (pseudonym). (Source: Ghost Island Mad News website screenshot)

“Thirty to forty thousand people saw the article within four hours, and that caught Facebook’s attention,” recalls A-hua. Because of this, he nearly couldn’t collect the $400 Singapore dollars he earned from the article. “Evan blamed it all on me.”

Thinking back to his time on the Big Durian platform, A-hua says in his heyday he could make more than $2,000 USD a month. He said the key was to copy articles from mainstream sources and then insert his own opinions. The most important thing was “knowing who your fans are.” For example, on Ghost Island Mad News “you would praise Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜), say that he had a hundred thousand supporters, then curse Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and the article would do well.” He voted for Han last year, though he says he doesn’t have a party or an ideology, and that writing political articles is just a hobby. When talking about others in his line of work, he admits, “sometimes you have to, you know, make things up.”

A SOUGHT AFTER COMMODITY BY BOTH PARTIES

For this upcoming election, A-hua said that the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) have all enlisted their own internet armies. He himself received messages from strange Facebook accounts, asking him to work for both the pan-blue and pan-green camps. The accounts all appeared to be foreigners, but when they realized that A-hua wasn’t interested, the accounts would vanish. These methods of contacting him are meant to leave no trace, since according to A-hua, “politicians are very afraid of being associated with these internet armies right now!” Because he had no information on who was behind the messages we could not verify his claims. He did say, however, that a Japanese media company had come to Kaohsiung to interview him, asking him to give analysis on Taiwan’s political internet battles.

Interest in recruiting A-hua stems from his rich experience in the field. He was a participant in the White Justice Union (白色正義聯盟) a Facebook page opposing the 2014 Sunflower Student Movement. In 2016 he joined the Association for the Promotion of the Proper Direction for a Lawful Society in the Republic of China (社團法人中華民國端正選風促進會) and helped to organize a pan-blue internet army. He also helped to create the Blue-White Sandals Counterattack (藍白拖的逆襲), a fan page with over 30,000 followers that supports the KMT. His original vision for the group was to strike a moderate pan-blue perspective, but as the members became more radical he decided to quit the group.

Even with years of experience, A-hua says the business is getting harder. He was once taken to court and fined more than 30,000 NTD for creating fake news. In the 2020 election year, he felt pressure from all sides, owing to national security officials and Han Kuo-yu supporters. Boss Evan has also put pressure on him: “Evan is Chinese, so if you criticize China he will delete your article.”

In his view, if you want to make money manipulating public opinion, then you have to make a lot of noise via images and videos on community platforms to attract a large number of fans. “If you curse someone harshly enough, then people will throw their money at you...right now, the green camp has more money.” In the January 2020 presidential election, A-hua planned to vote for Han Kuo-yu. After political articles were banned on Big Durian, he switched to ViVi (ViVi視頻), a video content platform from China, to continue to air his political views and conduct his business.

But how much can self-employed individuals such as A-hua influence Taiwanese public opinion?

The content farm with the greatest influence in the pan-blue camp is Mission (密訊). After Facebook blocked Mission, fan pages that usually shared their videos switched to sharing videos from Big Durian. We collected two months of statistics and found that a total of 460,000 supporters in 10 pan-blue Facebook pages posted 8,886 times, mostly from Mission and Ghost Island Mad News fan pages, of which 3,298 articles originated from Big Durian. From this data, we discovered that Taiwan content farms have a transnational character to them.

A-hua is optimistic about his prospects. He has 500,000 NTD in “start-up funds” to create his own platform for video content, modeled after Big Durian. He stressed that by working with coders from China, he could continue to dominate Taiwan's political information market at a quarter of Taiwan's cost.

FOLLOW-UP AND REACTIONS

On December 27th, after the publication of this article, Boss Evan finally accepted our request for an interview to discuss his views on content farms. He was only willing to conduct an interview via text, and not orally. When we asked if he was a Chinese citizen, he said it was a secret. We spoke for three hours, where he stressed that his work should be separated into two categories.

There is the Flashword Alliance, which is a self-publishing platform open to anyone; Boss Evan says the platform is committed to freedom of expression, and he takes no responsibility for any content. The other websites, KanWatch, beeper.live, and Qiqu News, are content platforms. In his view, the biggest content farm in the world is YouTube.

Below is a first-person summary of our interview with Boss Evan

A-hua once published a political article that hit number two on Facebook’s popularity rankings in a single day. I thought such politically risque content brought unneeded attention to the platform, so I banned it. At the time I knew of only two people who made political content, one was Holger Chen (館長/陳之漢) and the other was A-hua. That day I blocked both Holger Chen and Ghost Island Mad News, and deleted anything about Tsai Ing-wen, Han Kuo-yu, or Taiwan’s elections.

There are a lot of opposing political ideas on my platforms and I don’t advocate for any of them. I have no idea whether people who use my platform are being paid by the DPP or KMT. There’s too much risk in political content these days, so I deleted all content related to cross-strait issues or Hong Kong from my content farms. My good friend from Taiwan once told me not to touch politics. I didn’t pay too much attention because there wasn’t much political content, but now I’ve completely banned politics, and violators get deducted double revenue. But, I haven’t banned politics on the self-publishing platform. Everyone has free speech there, and if the DPP writes something I won’t ban it. There are DPP supporters there, but not as many. I am not trying to influence public opinion, and I haven’t taken money from anyone to write articles.

Who else is doing content farms?

There are two kinds of farms. One kind makes money by sharing trivial articles. The other kind has an agenda, what kind of agenda I don’t know, but there’s some kind of motivation behind their actions. Right now, I know about six major content farms run by Chinese; but the article you wrote only mentions the articles I personally wrote, and makes it seem like I run every content farm on earth.

Fan pages in Taiwan, aside from mainstream media, are all content farms. I know three major Taiwanese content farm companies, with a total of over 100 million followers. Of course, some of their followers are repeats. These companies work together with LINE and Facebook. I don’t want to say who they are, I’m afraid of retaliation. Taiwanese content farms are all companies, with ten or so sharing an office. You can’t get inside, so we don’t know much about them. I just write code for this platform, I don’t write content. Those big companies have a lot of employees, and they do everything themselves. These content generators are the ones who are truly scary, because whatever they write, their boss says, okay. These companies are all Taiwanese, and they have bots that spam people. Spam bots aren’t my domain... I don’t really use LINE.

How do you suggest we look at information from content farms?

Farms are just farms, don’t think about it too much. Most content farms are just trying to profit, and have no interest in politics. The political content that appears in content farms is only there because it just so happens that a member has that political view, and doesn’t represent the view of the managers. Political thought is often very extreme and can’t view things objectively. People just take some content that aligns with their views and write about it, and they tend to miss the forest for the trees. For example people have strengths and weaknesses, and people who like them will write about their strengths, people who hate them will write about their weaknesses. It seems like both sides are right, so what’s the problem, but if people write too much, they become biased.

I hope you can write objectively and fairly. That essay about yam leaf milk, with 830,000 views on YouTube, is more than the number of clicks I get on my website on any given day. The article only talks about me, but please also say something about the number one content farm, which is YouTube.