Louder than Bombs: The Photo Negatives Exposing the Truth of the Tiananmen Square Protests

The Reporter interviews legendary Chinese photographer Xu Yong, a witness to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and the author of the new photo book Negative/Scan.

By Yu Chih-wei (余志偉)

Photography by Xu Yong (徐勇)

This piece first appeared in The Reporter in Traditional Chinese and is translated and reprinted with permission of the publisher.

Thirty years after students rushed into Tiananmen Square to demand greater democratic accountability, the political atmosphere in contemporary Chinese society is more oppressed than ever, and people err on the side of caution when talking about the historic event in public or private. In fact, for many young people in China, the student protests that lead to the crackdown on June 4th are of no concern to them, or they're simply not aware of the event's existence.

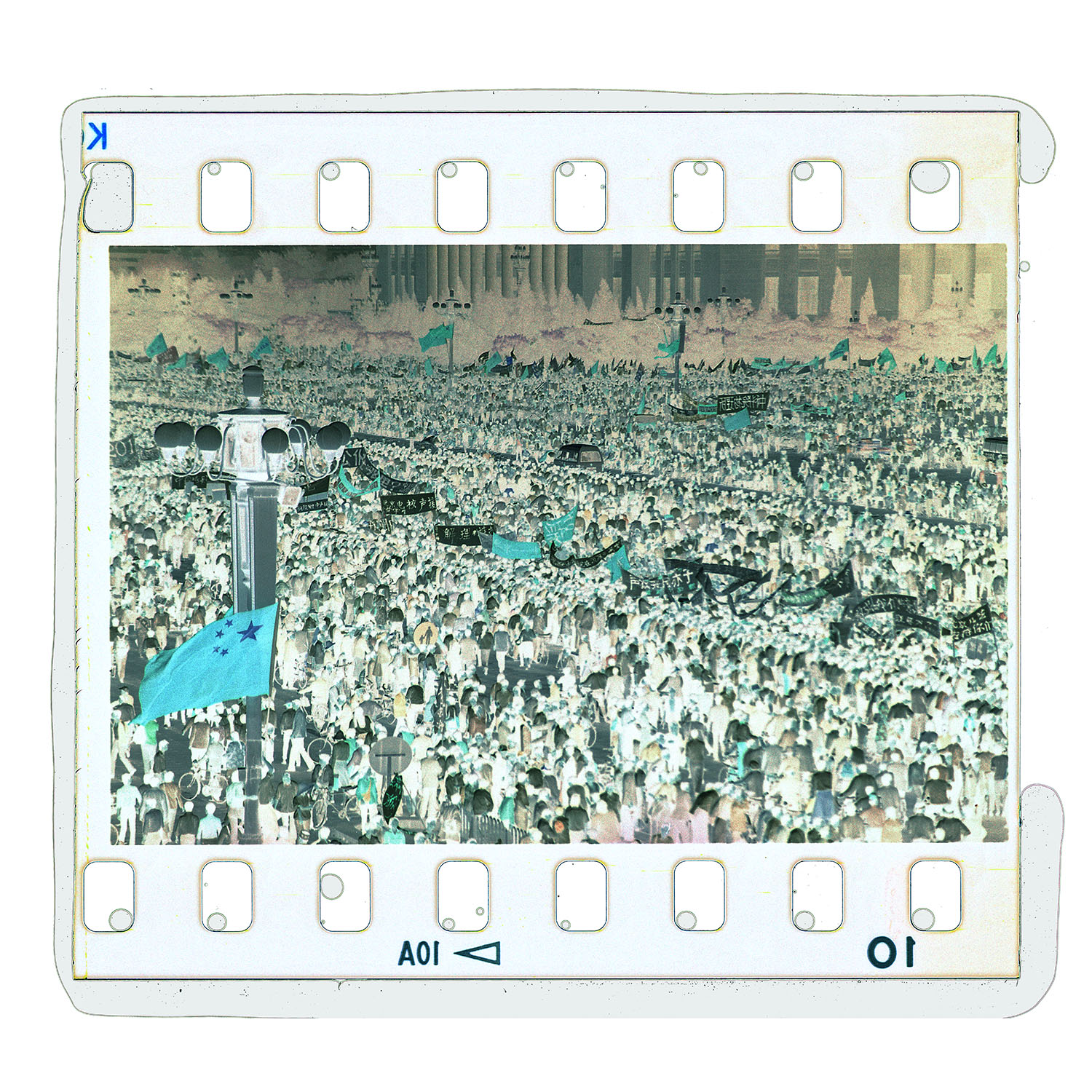

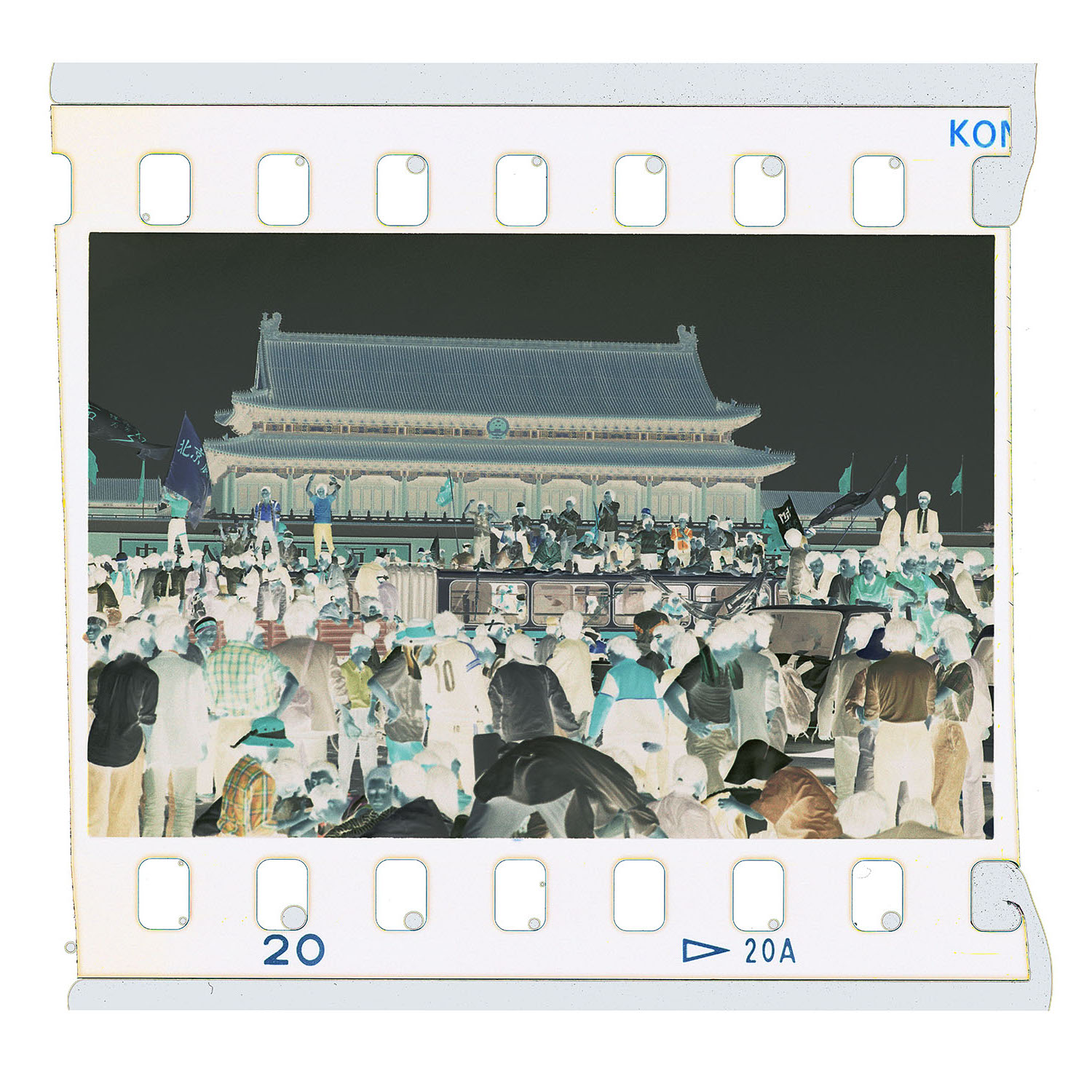

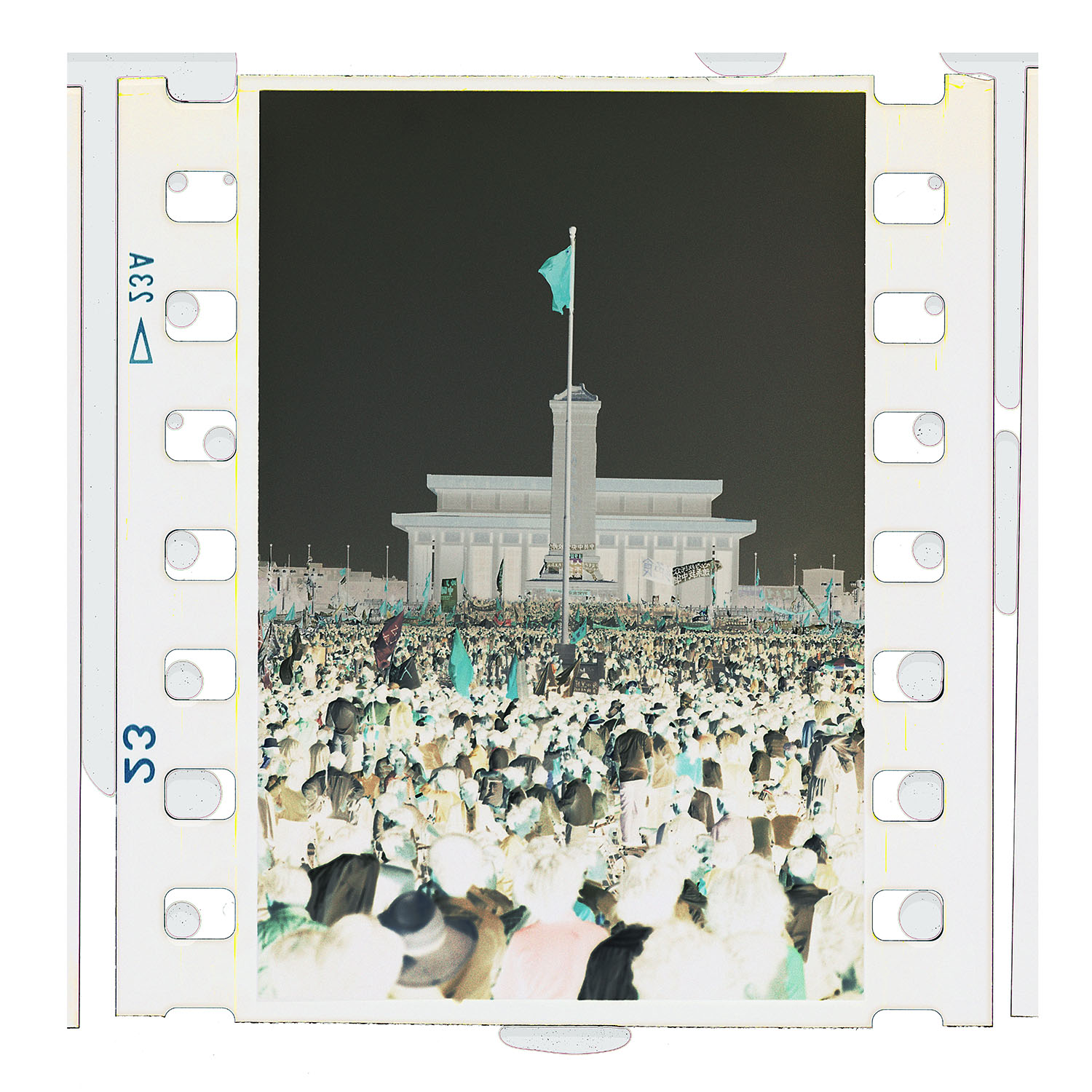

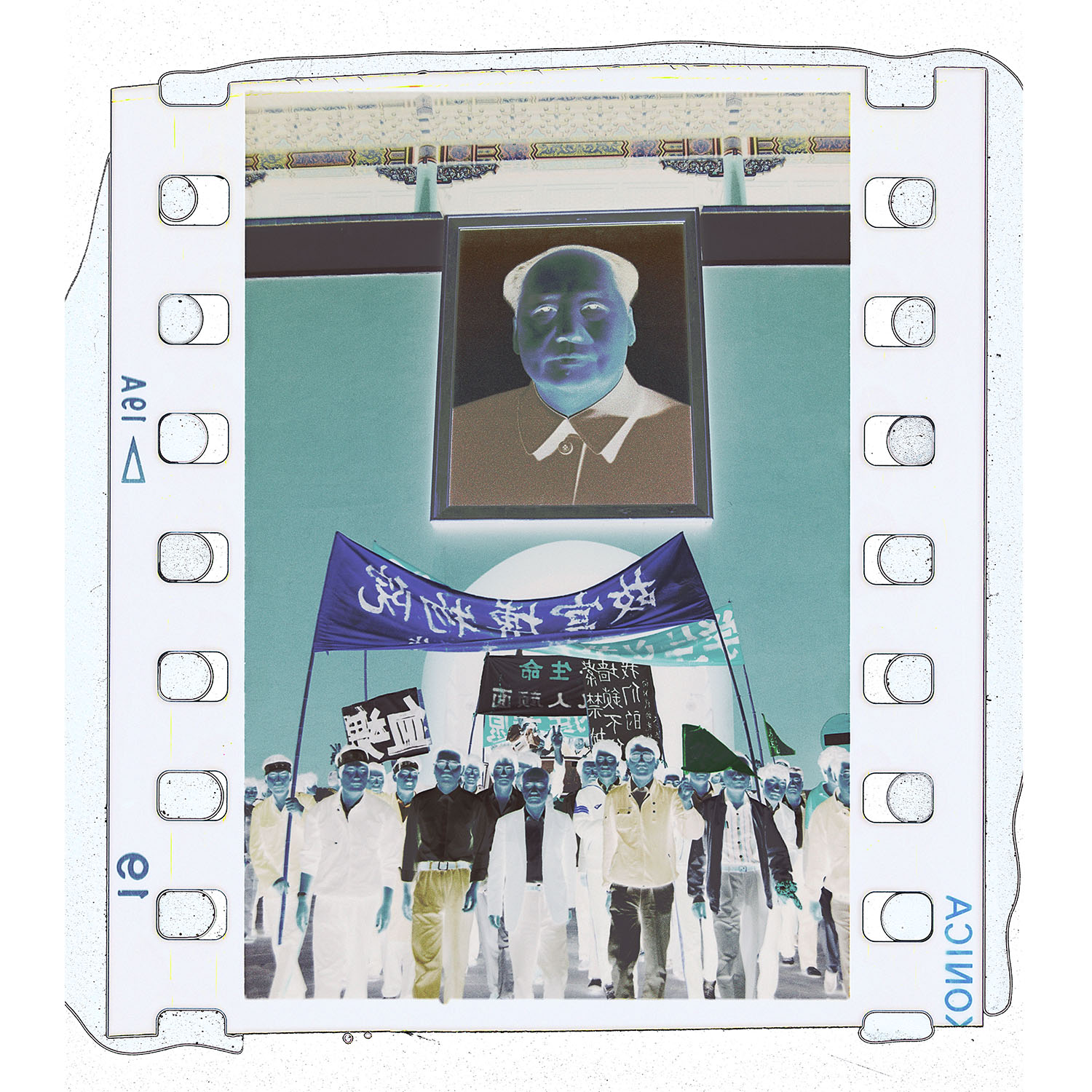

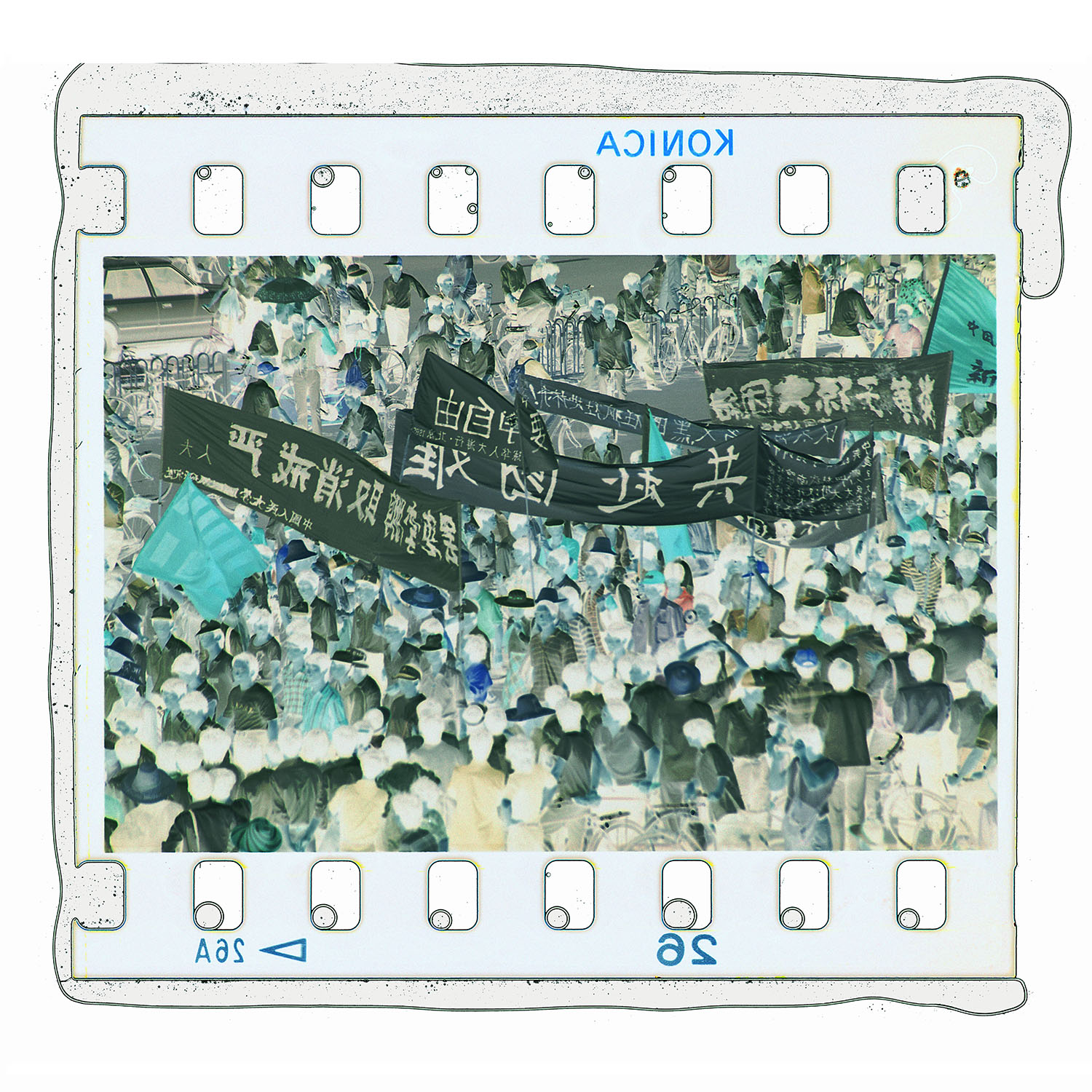

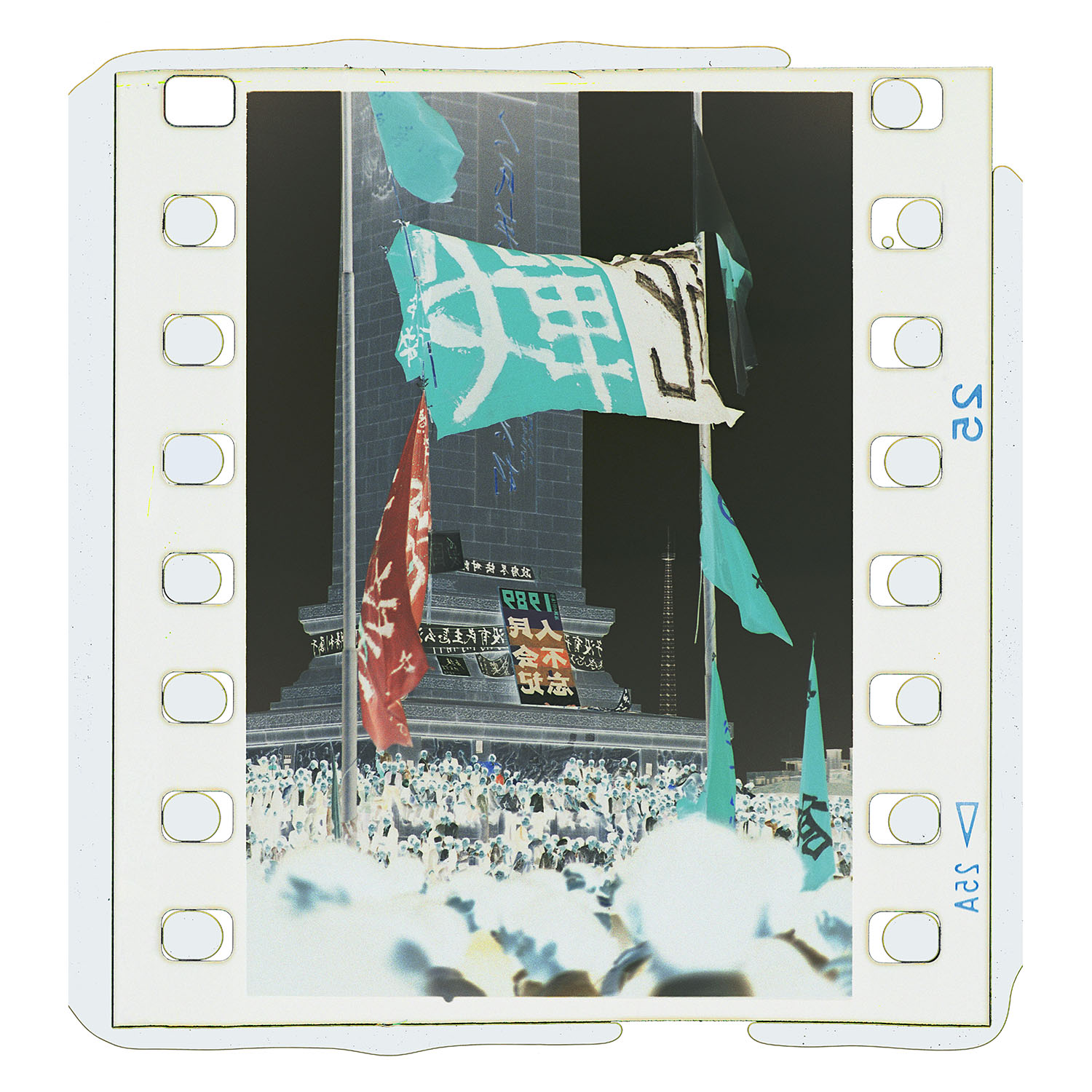

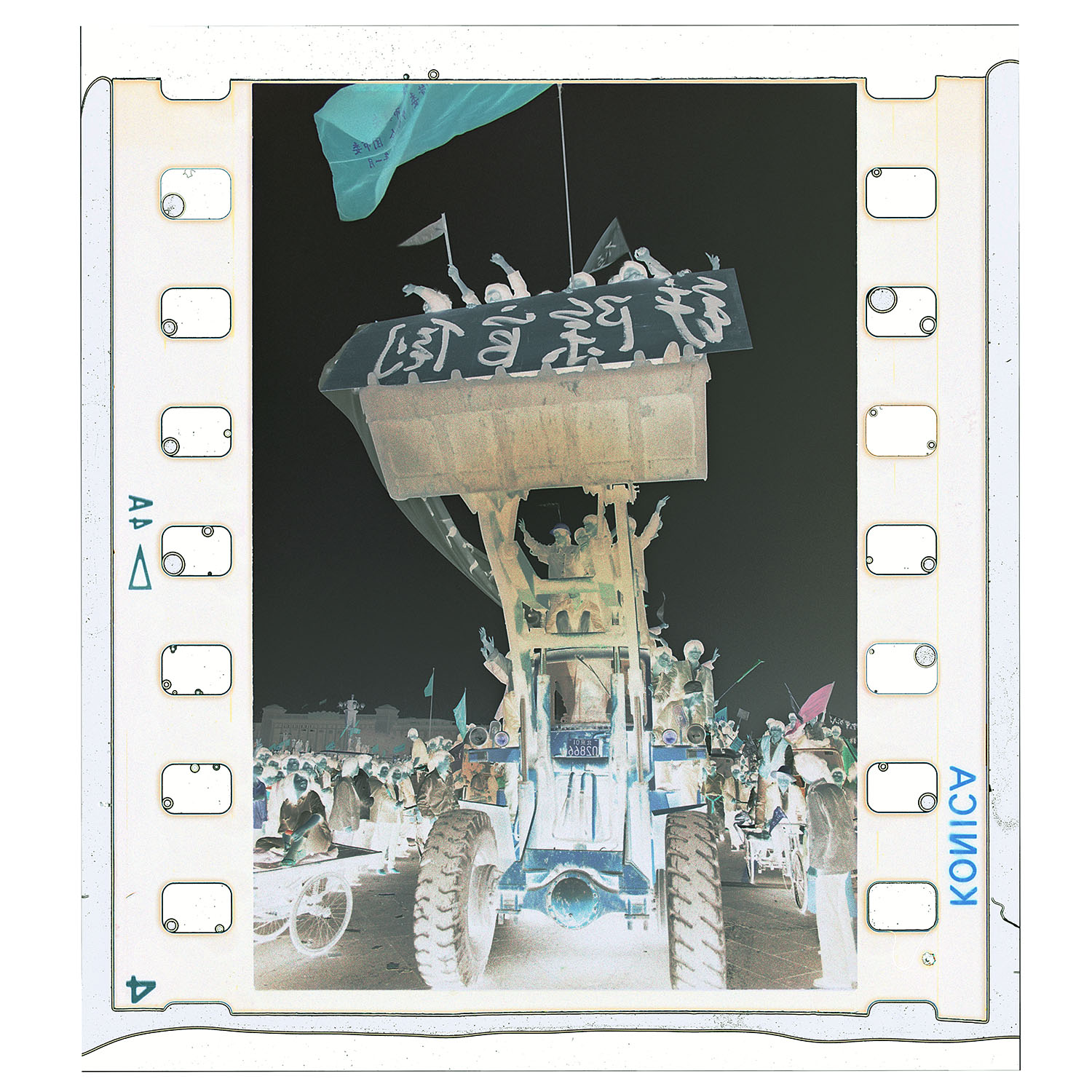

65-year-old photographer Xu Yong (徐勇) wants to change that. Over the past few years, he's collected two series of Tiananmen Square images he captured at the time. Xu has compared this curation process to a deep, underwater explosion -- these images lay dormant in the public's subconscious, and by exhibiting these photo negatives 30 years later, they send ripples of truth to the surface.

In December 2014, Xu Yong, a photographer based in Beijing, put together a photobook of film negatives he captured during the infamous Tiananmen Square protests. He held off publishing the images for years.

On the eve of the 1989 protests, Xu was a 35-year-old photographer who just left a prime position at Beijing's largest advertising agency.

Chinese society was still recovering from the decade-long Cultural Revolution, and the ideological trends of Deng Xiaoping’s (鄧小平) “Reform and Opening Up” were finally taking hold. The students who first gathered in Tiananmen Square were only there to commemorate the death of Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) — a former general secretary who staked out a position as a reformer within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). But the gathering soon morphed into a full-on student protest movement.

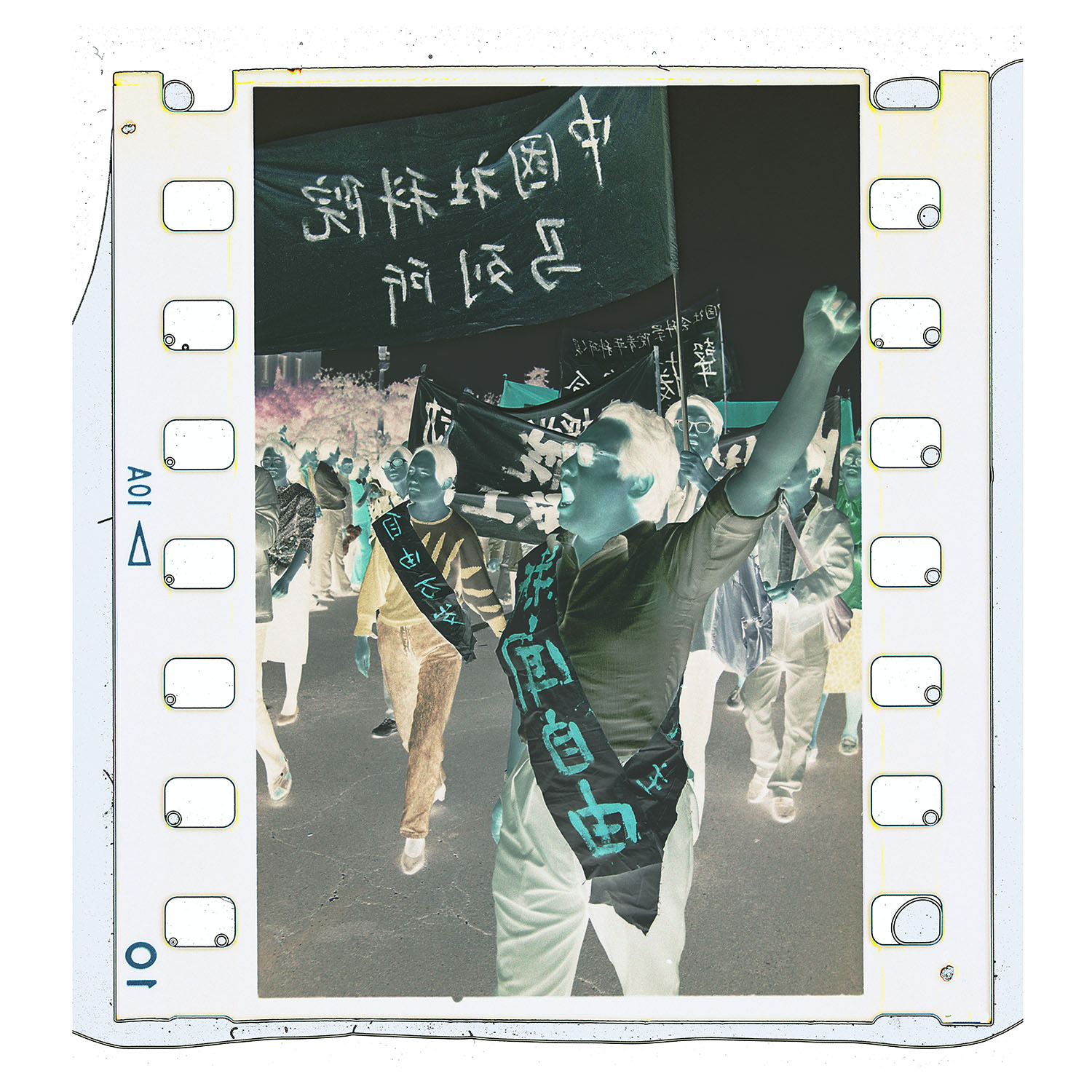

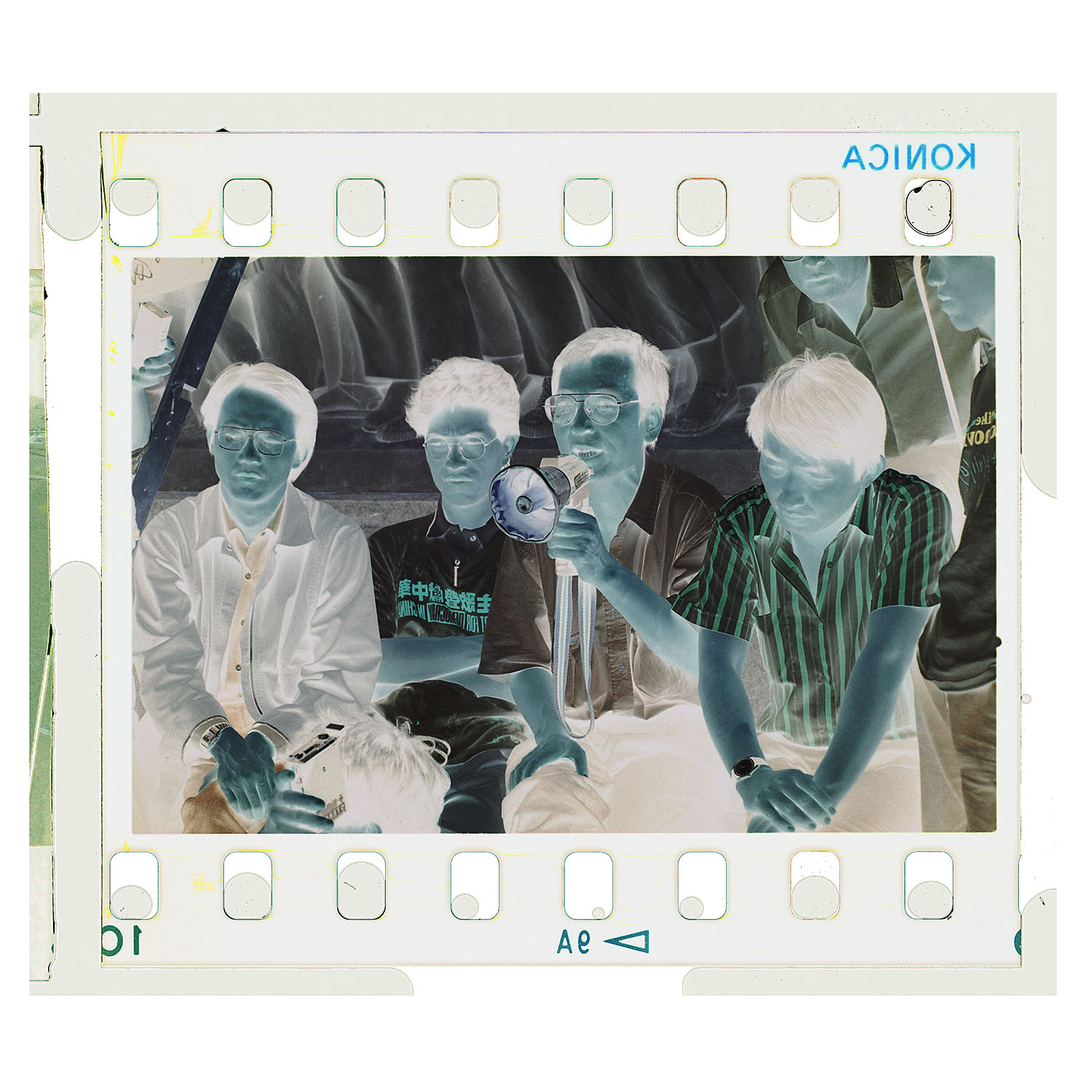

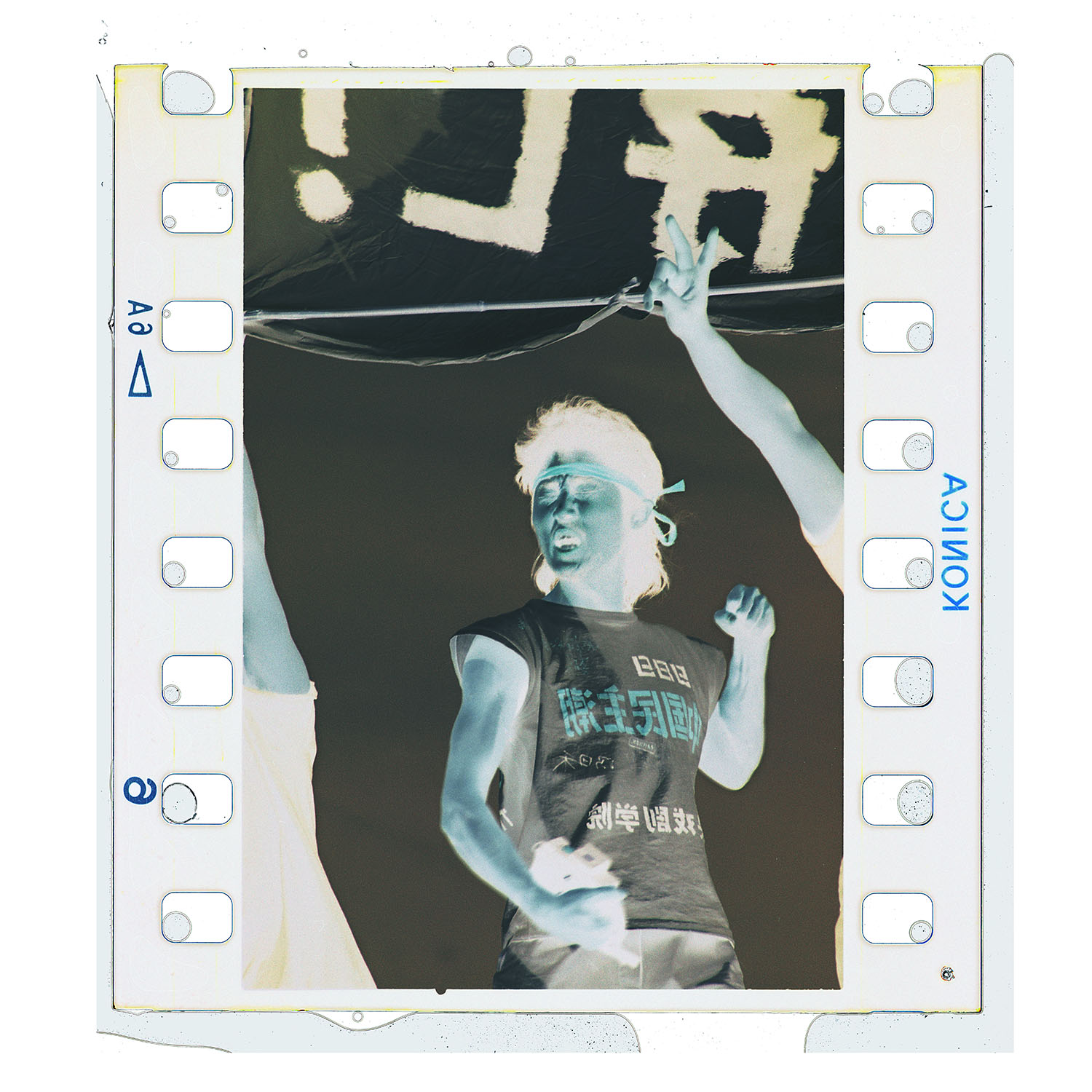

Xu Yong was deeply affected by the protests. He took his bulky camera to the square, and captured images of young faces full of idealism and high hopes, as well as ardor and anxiety.

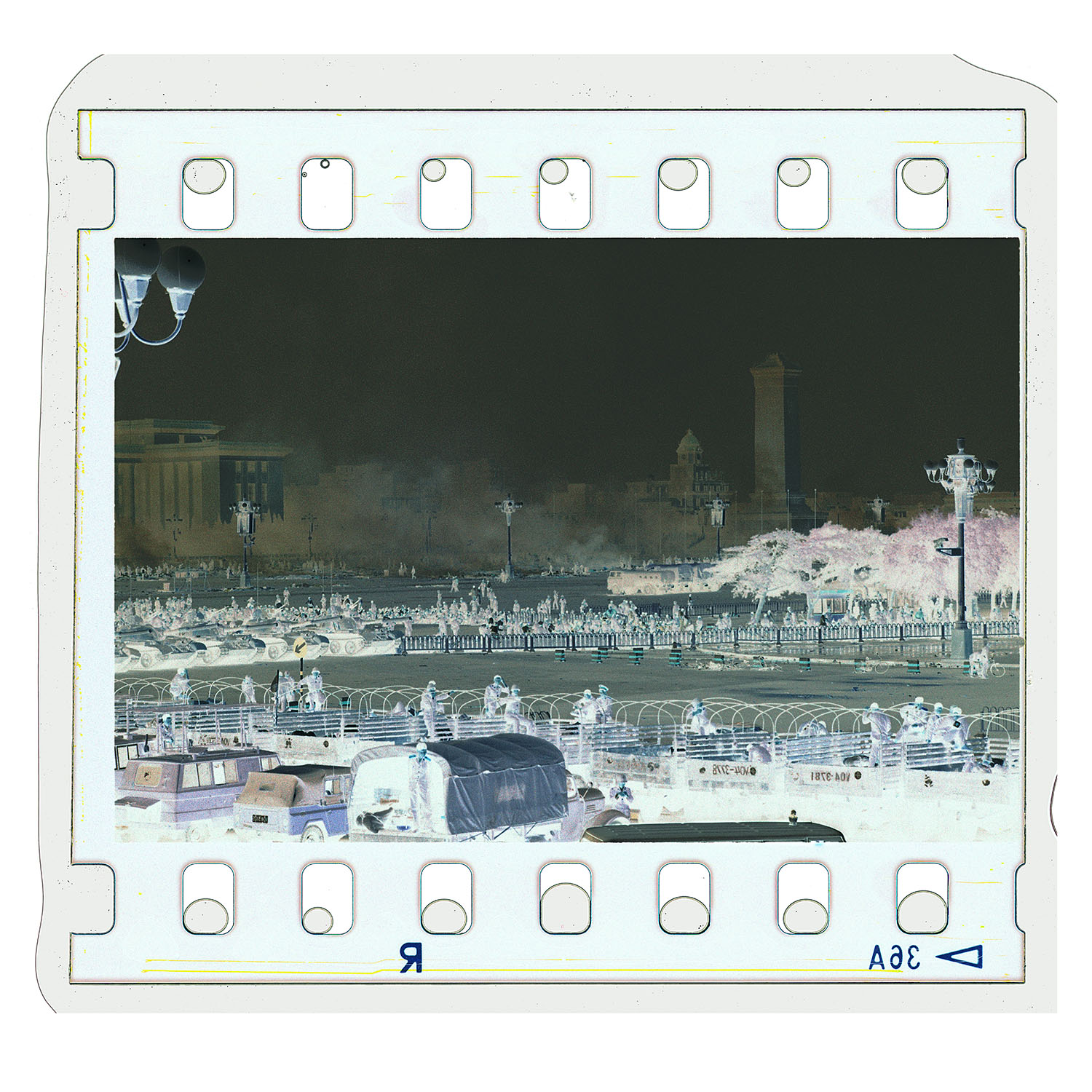

With the help of Hong Kong's New Century Press, the photo negatives resurfaced in a photobook called Negatives. In a recent interview with The Reporter in Beijing, Xu disclosed a new series of photo negatives to publish — Negatives/Scan.

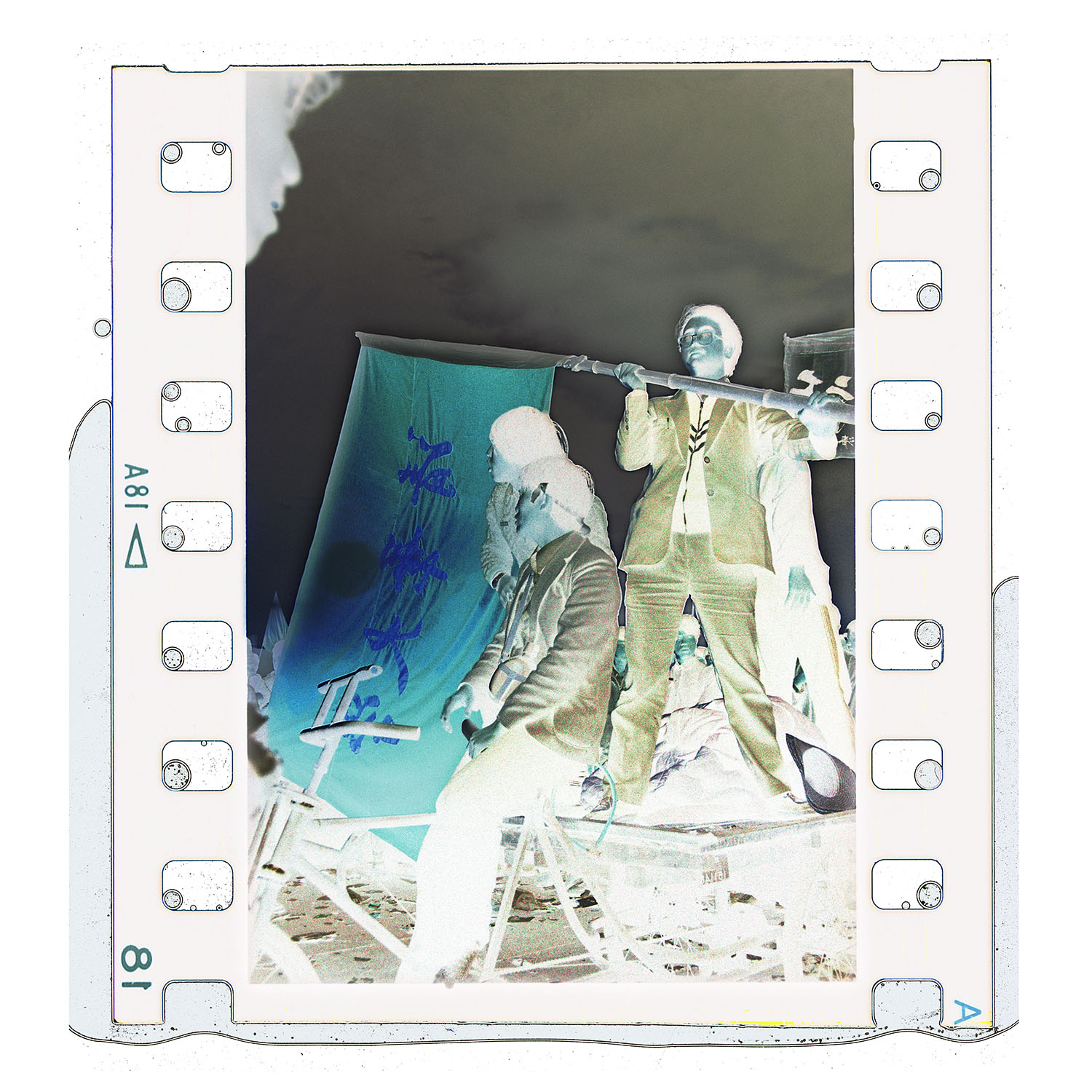

In this new collection, the film stock and the content appear to become one, and the images retain the complete 35mm film roll outline, as well as traces of local oxidation and discolouration from the film washing process. In effect, the physical properties of the film are fully emphasized and the performance space of the content is limited.

The images were first shown at an exhibition at the Hamburg Central Library at the invitation of the University of Hamburg’s Department of Chinese Languages and Culture.

Using film negatives to challenge censorship

Xu began thinking about a new series shortly after publishing Negatives. He says the narrative nature of traditional photography and the conceptual nature of contemporary photography are like two intersecting circles. When the circles overlap, they show the artist’s different modes of thinking and values.

Because factors like time and the political environment in China are changing how we view the Tiananmen Square protests, using inverse colours and digital tools on our computers and phones could be a way to break through those barriers.

Xu recommends viewers to look at the Negatives/Scan series from their computer, and use their mobile phone as a decoder to invert the photo negatives to a standard colour scheme. If you use an iPhone, head over to Settings, choose “general” then “accessibility” and select “display accommodations”. Under “Invert colours”, tap the “classic invert” slider, then select the camera function to view the photos.

The image proportions and picture order of Negatives/Scan say much about Xu Yong’s feelings towards Tiananmen Square and the narrative nature of his work. The series is an attempt to weaken his subjective viewpoint and highlight the conceptual nature of the pictures. Old images seem new, and help to expose the government’s attempt to cover-up the event and erase history.

“The fact that these negatives physically exist can’t be obscured or altered, and their value has only proved more significant over time,” says Xu.

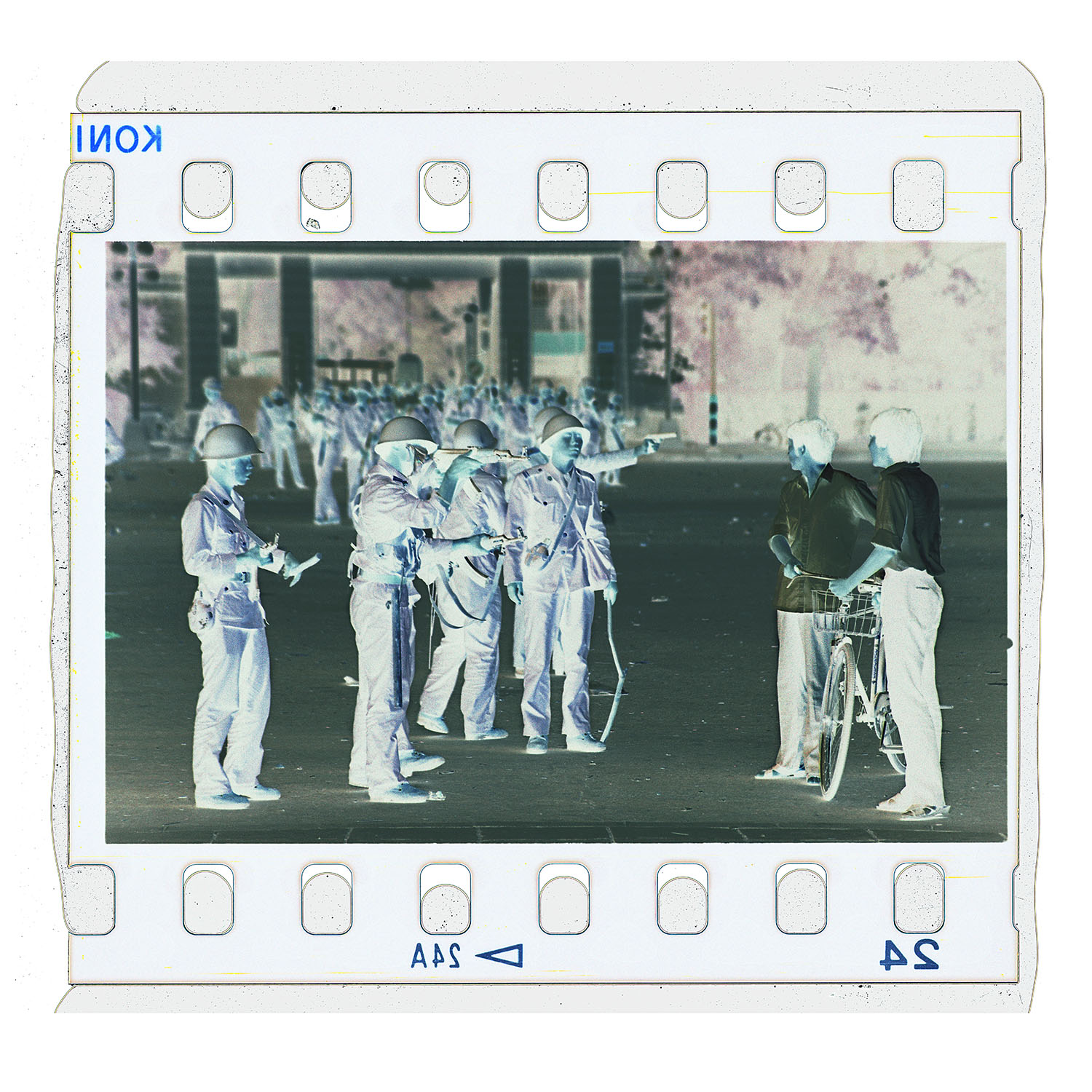

Photos of the protests were seen everywhere in 1989, but they rarely saw the light of day in China. Even publishing words related to the Tiananmen Square protests could lead to criminal liability. In publishing these taboo images, Xu doesn’t directly address the content of the images, but deliberates on how to deliver the immutable qualities of these images.

The bloody conflict of the Tiananmen Square massacre does not appear in Negatives, and only the final image of a tank clearing up the square on the last page—ominously marked as “page 64”— portends the end of the student movement. In Negatives/Scan, the penultimate image also points to a menacing end for the protesters, with a group of soldiers pointing guns at two unarmed men with a bicycle. Xu doesn’t hide any implicit messages in these photos.

Confiscated on the way back to China

After photographing the events of Tiananmen Square, Xu went back to a project he began in 1985 — Hutong 101. By the end of June 1989, there was an oppressive silence in Beijing, which affected Xu's mood while shooting the series. He was inspired by his former work at an advertising agency, and his images scrupulously avoid typology, and the focus is on consciousness and flow.

Hutong’s are normally full of hustle and bustle, but he deliberately leaves people out of his shot. In the book’s final image, he presents a three generation family in a Hutong courtyard, with their solemn eyes staring straight into the camera lens.

Hutong 101 was one of the first collections of contemporary personal photography in China after the Cultural Revolution, and was serialized in Japan by two of the country’s most venerable publishing houses.

While Hutong 101 features some clear structural and conceptual thinking, Xu’s work on Tiananmen Square is all about recording the events of the protest. Xu was quite different from the foreign photojournalists at the scene; he was a local taking photos, and he brought a different set of emotions and sensibilities to his work. Xu doesn’t believe that photography is solely a medium to communicate information, and he used his training in traditional, modern and advertising photography techniques to bring out different aspects of the Tiananmen Square protests.

In addition, the price of a colour film roll was equivalent to one-third the monthly salary of an ordinary worker in Beijing. He needed considerable self-discipline to press the shutter button, and would only take two to three quality shots for each scene. If the Tiananmen Square protests happened today, Xu says his photo-taking style would be quite different.

Xu attended two exhibitions of Negatives in Germany and France in 2014, and photo books were published in preparation for those events. When he goes to Hong Kong (or entrusts a friend to go) to pick up newly printed copies of the books, he tries to bring back three or four copies back to Beijing with him. He has to be extremely careful when he passes through the airport though. He’s tried to send books via Fedex, but they were all confiscated by customs.

“The Chinese authorities know about my exhibitions. They probably think I’m some weirdo, but overall, I don’t get into too much trouble,” says Xu.

“In China, I can only give these photo books to friends I really trust.”